In his much-quoted opening of Dublin 1660-1860, the architectural historian Maurice Craig describes how one of the most momentous events in history, the taking of Byzantine Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, had a side effect with unexpected consequences.

Byzantium, a huge Christian empire and the surviving eastern half of the old Roman Empire, boasted a continuous one-thousand year history, dating back to its foundation by Constantine himself.

Its sudden defeat and collapse was regarded with shock, as an catastrophe in the Christian west.

The defeat of the once mighty Christian Empire led to an exodus westwards to Italy, as Craig puts it of- “refugee scholars… each supposedly clutching a precious codex”.

Famously this injection of previously “lost” classical knowledge led to the Italian Renaissance.

We recognize better today that Arabic and Turkish scholars had in fact protected ancient Greek works and knowledge. Indeed they did, had already done most of the best translation and interpretations of classical works.

It ‘s true also that many other factors that led to the Renaissance were already in train, well prior to the collapse of Constantinople.

Nonetheless, the arrival of refugees carrying classical knowledge, previously forgotten in the west, was doubtless one of the main drivers of the Renaissance and everything that was to follow.

The collapse of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire changed global history. Christianity had been born in the Middle East but now Islam now reigned supreme. The Ottoman Empire ruled in the Balkans and even menaced the gates of Budapest and Vienna. Europe inherited the mantle of the Christian continent. Vital European trade routes to Asia were now blocked, launching an era of Western maritime navigation and exploration that would usher in everything from Christopher Columbus, Magellan and Vasco de Gama (and much later to Captain Cook and global 19th century colonization.)

Ireland in 1453 was of course was on the periphery of Europe, isolated by geography from the currents of great European events, and far, far less developed. Notwithstanding the scholastic achievements of monastic Ireland, most of the country was run by Gaelic chief and small kings, with almost Bronze-Age values and world-view. While in the tiny and fragile Anglo-Norman colony of 1171 had developed into an only slightly-less-fragile English colony of 1453. Accordingly, given our peripheral status, it took some two hundred years for the ripples of the Renaissance to wash up on Irish shores.

Or, as Craig memorably wrote….

“Like a seismic ripple, or the last reverberations of a tidal wave, this great Levantine catastrophe spread its rings until, two hundred years later, a little wave washed up on the sands of a remote western shore, and James, Duke of Ormonde, stepped out of his pinnace onto the sands of Dublin Bay. The Renaissance, in a word, had arrived in Dublin. It was July the 27th in the year 1662”

So Craig chooses the year 1453 as a punitive “spark” for the Renaissance, and 1662, with the return of James Butler, Duke of Ormonde coming from sophisticated France (in exile with the deposed Stuarts) as the moment when Ireland stepped out of its long Medieval age, and embraced, belatedly, at least some of the features and ideals of Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Early Modern thought. It was of course Ormonde as Viceroy who began to lay out Dublin as a classical city, insisting for example that buildings were pushed back from the river and so creating the quays along the Liffey. The medieval style was of course to build houses right up to the edge of rivers and canals, (as we still see in Venice and Bruges today)

In visual terms, and in built culture, Ormonde’s influence and French-acquired tastes meant classical architecture, with Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns. It meant pediments and arches, and triglyphs and metopes and Greek key patterns on lintels. It meant domes and cupolas and all the other exciting new-fangled (or rather old-fangled) box of classical tricks.

The effect was extraordinary. Prior to 1660, Dublin was a dowdy, old- fashioned medieval city, with narrow lanes and alleys cut through the sort of solid urban mass, typical of Middle Ages cities .

By 1860, it was one of the most elegant neo-classical, capitals of Europe, with wide streets and scores of spectacular, set-piece public buildings in the Neo-Classical style.

It goes without saying, there were multiple political, religious, dynastic and economic factors in play also. Nonetheless, Craig’s introduction illustrates a beautiful example of what we might call the “Ripple Effect”- namely how great events in important but far-off places (Paris, London, Florence and Constantinople) eventually wash up on distant shores. The Byzantine collapse had a huge, incalculable, impact on western history, we all know that. But it had a huge impact also on western visual culture. This interplay, between the great currents of history and the less epic, but still engaging changes in visual culture, art, architecture and design, fascinate me and I believe make a rewarding study.

Yet another interesting example, of the Ripple Effect I’d like to present to you comes from Revolutionary France and its titanic battle with Britain. Are you ready?

As we all know, in 1798, Revolutionary France was at war with England. Like the earlier war between the Ottoman and Byzantine empires, another huge battle was underway, between ideological foes, that would affect the entire world.

The Revolutionary French executive, the Directoire, had some tough decisions to make. They undoubtedly possessed a larger and superior army to the British. But the better British navy (and the resulting British control of the seas) made any serious projection of French military and economic power difficult.

Naturally, this was pretty irritating. One particular source of French grievance was British dominance of the huge Indian subcontinent, along with its huge, lucrative markets and vast resources.

Due largely to the British navy, the French were unable at that point to mount a direct invasion of Britain. So, they instead sought to strike her most vital trade routes, to India and the East Indies. By doing this they also hoped to destroy the all-powerful British East India Company (indirect, corrupt but de facto rulers of India) and for France to seize European influence and trade in Asia from her hated rival.

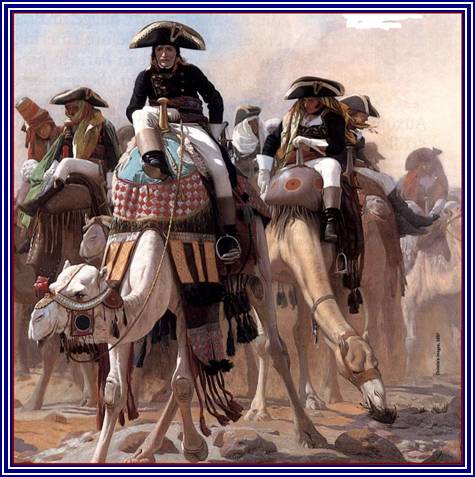

To this end, and to promote French trade and prestige in the Orient, the Directoire adopted an ambitious scheme for the French conquest of Egypt. This plan was proposed by their most ambitious and best-known general, one Napoleon Bonaparte,

The campaign was soon approved. Napoleon himself became commander. He took many of his former veterans from the Armée d’Italie and forming them into a new force, le armée d’Orient. In May 1798, the army shipped from Toulon, and successfully evading the British Mediterranean fleet. They needed to refuel and re-provision mid-voyage at Malta. When the rulers of the island, the venerable Knights of St John, refused permission, rather unwisely, the French simply conquered Malta instead, ending a regime that dated back to 1530.

By July 1st the French army had arrived in Egypt, disembarking at Alexandria.

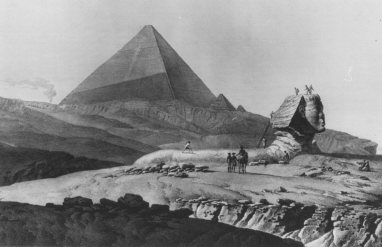

Napoleon defeated the local Mamluk rulers, notably in the famous Battle of the Pyramids. Soon the French army was victorious and Bonaparte’s control of the entire, huge country was complete.

As always, the legacy of Bonaparte in Egypt is ambiguous, and hotly debated. Although he was nominally a senior army officer working for the French Republic (with its democratic, egalitarian ideals) Napoleon – true to form- soon made and styled himself an absolute ruler, (much as he had previously done in Italy.) On the other hand, he did introduce some real benefits to Egypt, such as newspapers, new colleges, printing presses, and reforms to education, administration and so on.

(Above: a contemporary engraving picture of the Institue of Egypt, at Cairo,founded by Napoleon Bonaparte. and modeled on the French Accademie of Paris)

He was in serious danger when the British took control of the seas off the coast, (cutting off his supply routes and making reinforcements impossible)

A dangerous popular revolt in Cairo in October 1798 also threatened to destroy the entire French project and army and trap Napoleon himself. The French only narrowly overcame the uprising. After bitter street-to street fighting many of the rebels were eventually trapped in a large square. French reprisals were predictably savage.

The next threat came from a double attack by the Ottoman Empire. They sent two armies, one by land, across the desert from Syria and another by sea from their colony on Rhodes. Napoleon pre-empted or circumnavigated this dual threat with a counter attack into Palestine and Syria itself, taking Jaffa and then Acre, like some medieval crusader-king. Indeed (like most former crusaders) French conduct in victory at Jaffa was barbaric. Countless innocent civilians were slaughtered.

In any case, with his army strickened by plague, and soon outnumbered he was now unable to press home the military advantage and retreated back to Egypt.

Napoleon managed to get some of the injured and the plague victims back but many perished. A popular contemporary image, disseminated by the ever -impressive Bonaparte propaganda machine) was of the great general moving among his sick men, bravely and without fear of infection, selflessly touching and comforting them.

above: Napoleon moves among the sick, during the campaign.

Napoleon, again, always a master of propaganda, also made sure to stage his return to Egypt as a triumph, presenting the Syrian/Levantine campaign as an outright victory. His return even had a Roman-style “triumph” a parade complete with the symbolic palms of victory.

Nonetheless, following his recent setbacks and especially after Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile, Bonaparte realised that further French glory in Egypt and the Middle East was now unlikely.

Above: 19th century depiction of the Battle of The Nile. Nelsons’ victory made the French supply lines and reinforcements impossible. It effectively frustrated the cherished French ambition to dominate the eastern Mediterranean and made their position as Egypt’s ruler untenable in the long-term.

Knowing he was unable to further expand in the region, Napoleon soon returned to France, leaving most of his force behind in Egypt.

Despite one final victory for the French left in Egypt, (at the Battle of Akabir) they still faced the eternal problem of the British navy, making expansion and re-supply almsot impossible.

Although their time in Egypt was therefore now limited, Napoloeon himself showed an astute and cynical sense of timing. French victory at Akabir boosted his prestige even as he was sailing away to France. He made straight to Paris. By November he was in the middle of a coup de Etat. By 1804, he went the last step and declared himself Emperor. The General and Field Marshall , soon became the ruler of Europe, and an Emperor in the image of Augustus and the Caesars. The rest, quite literally, is history.

****************

What was it all for?

Apart from severing British trade routes to the east, and hugely expanding their sphere of influence, the French campaign had other war aims. These are very interesting.

One aim was the resurrection of a dream of many rulers back to the Pharaohs, Ptolomy and Alexander the Great, namely a canal from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and thus the Indian Ocean. This would of course allow trade between Europe and Asia, without the need for the huge sea voyage to circumnavigate Africa. The best route would link Port Siad on the Mediterranean to the city of Suez on the Red Sea: in other words- the Suez Canal.

It goes without saying that any power controlling such a canal would hold an enormous strategic and economic advantage.

This ambition explains one of the most distinctive features of Napoleon’s campaign preparation: the enormous number of scientists, artists and scholars who accompanied the army. There were over 160 in total, including mathematicians, geographers, geologists, cartographers and engineers.

Many of these were of course detailed to survey, take and analyze samples, map, and design and plan the canal.

However, Bonaparte had further, even loftier notions for the occupation, namely the study and documentation of fabled Egyptian civilization.

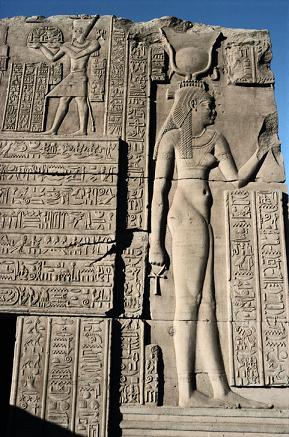

Those who came into contact with the mysterious and majestic monuments of ancient Egyptian civilization were inevitably affected. Even back in 30 BC, following Octavian’s annexation of Egypt, a Roman magistrate was thus seduced. He built his tomb in the form of a steep-sided pyramid.

But that was all a long time back. By the early nineteenth century Europeans had little knowledge about the wonders of ancient Egypt. Napoleon resolved to change all that. Scores of artists and scholars were attached to his army, including painters, historians, architects, archeologists, linguists and classical scholars.

These scholars (called “les savants”) compiled a vast, enormous report on its land, history, culture and artifacts, called Description de l’Égypte.

The vast amount of information and material they brought back effectively re-launched the entire western fascination with Egypt, and of curse the formal academic study of Egyptology.

All things Egyptian soon became a cult, an infatuation. In Paris, capital of European sophistication, everything from clothes to wallpaper was influenced. Hairstyles, make-up, furniture design, architecture and every other aspect of style and design were all affected by the new craze.

Parisian and French fashions were soon copied in Britain and around Europe. The salons of London, Bath and Cheltenham soon looked much like those across Channel. Fans of Jane Austin may be sure she sat on many a modish Egyptian-styled chaise-long.

The Goodie Bag.

Napoleon’s previous conquest of Italy had of course included some of the most spectacular looting in history. Hence the bulging treasures of the Louvre, the largest and richest single collection in the world. Note the Mona Lisa and six other Leonardos’ in the Louvre (and not, say, the Vatican or Uffizi)

The Lourve today does indeed have a stunning collection of Egyptian artifacts, one of the very best. But oddly enough, and despite his intentions, less than 50 (from 50,000 Egyptian artifacts) date from Napoleon’s campaign. Although the French did collect enormous amounts of tablets, columns, sculptures and other artifacts, much of their hoard was intercepted and gleefully seized by the British fleet. (One can only imagine how the future Emperor felt about this)

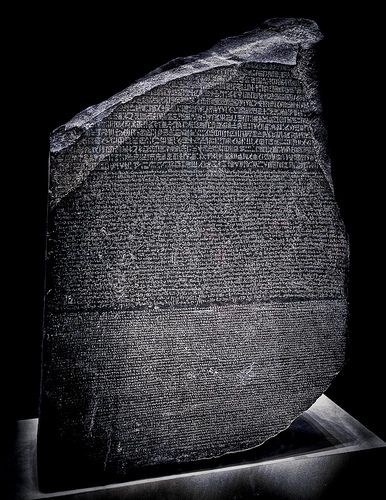

Napoleons return to France left the remains of the French army and administration in Cairo but they were eventually forced to surrender. During this handover of power the British acquired further items. One of the most precious and significant was the legendary Rosetta Stone, now in the British Museum. It would in time, famously, provide the key to the age-old mystery of deciphering hieroglyphics.

The Roseta Stone, (above) Bearing a decree by the king Ptolomey, in Memphis 196 BC. The Stone was moved from its originally ancient site to be used as building material, then re-discovered in 1799 by a French soldier attached to Napoleon’s campaign . Because the stone contained an identical, or near-identical text in three alphabets- Greek; Demotic and Hieroglyphic- it eventually proved the key to solving the age-old problem of deciphering ancient and mysterious hieroglyphics.

The Legacy of the French Campaign.

Few today would condone such aggressive imperialism. But for all the bloodshed, oppression and suffering, the French occupation of Egypt, the scholarship that accompanied it did have at least two tangible benefits. However forcibly, it introduced Egypt to secular enlightenment values and ideals of the west. (Values and ideals that are of course still controversial and fiercely contested in Egypt to this day)

The second benefit, again at huge cost (of looting and dispossession) was to open up and educate European to the wonders and glories of the most ancient civilization in the world.

So what about the ripple effect? And Ireland?

We know 19th century Europeans knew little of ancient Egypt until Napoleon’s campaign opened their eyes again.

Then, as we have seen, almost immediately following his invasion, as artifacts, copies, prints, engravings and other images flooded into western capitals, the huge craze for Egyptian art and architecture spread first in France, then to Britain and beyond.

In architecture the style we see from this first early 19th century period is a sort of Egyptian Neo-Classicism.

There are very few pyramids in evidence in this style. Rather buildings tend to a fusion of the previous classical style, with a sense of line, mass, and proportion clearly influenced by Egyptian temples, most especially inspired (I’d venture) by the iconic structures at Luxor, (formerly known as Thebes.)

The elongation of some elements, and the massing of others is hard to describe perhaps, yet impossible to mistake. At their best these buildings are stunning.

In Dublin, we have a small, but lovely handful of Egyptian Neo-Classical buildings. Two stand out by far. One is the fabulous edifice dominating Earlsford Terrace. There was some sort of building here in 1865, originally constructed for the Great Dublin exhibition of that year, much of which took place on the Iveagh gardens directly behind. But this first structure was substantially altered and redeveloped, including the addition of the spectacular façade we see today, as it was converted for other use as one of the main building of the Royal or Catholic University, (later UCD.)

Following UCD’s move to Belfield campus in the 1960s the hall slowly wound down its university function and is today the National Concert Hall, home to the National Symphony Orchestra.

The architect responsible for the conversion and the amazing façade was one Rudolf Maxmillian Butler. Despite his Teutonic-sounding name, he was an Irishman, albeit a well-travelled one. Perhaps his father had a taste for Wagner and austere Germanic spectacle, which left a mark on the future architect. There is plenty of romance and drama in this wonderful building.

Another Egyptian Neo-Classical building in Dublin and undoubtedly the most impressive is the stupendous Broadstone Railway Station. The designer was John Skipton Mulvany. I write about this building, and its surrounding quarter quite a lot in the Hidden Dublin book, because there is so much history in the immediate area, often overlooked today.

But on the building itself I don’t think I can improve on Craig’s description.

The great man, who I quoted so liberally at the head of this little essay, describes Broadstone as “the last Dublin Building… to partake of the sublime. “

Here it is…

There are other Egyptian inspired buildings and passages of detail in Dublin,

Perhaps less grand, massive or fabulous but still well-worthy of our attention.

This temple-style structure on Ringsend Road (by the bus depot) shows a clear influence.

And of course there was a second flourish of Egyptian-influenced detail, line and proportion in the art deco era, and indeed in the severity of Fascist architecture.

Can you see it in these details, from two separate buildings on Kildare Street?

Department of Trade and Industry, designed R. Boyd Barret.

The Refuge Assurance Building, no 4, Kildare St. . The original house is a brick Georgian structure, but this wonderful minimalist, Egyptian-deco facade was added in 1935, by architect Fredrick Hayes.

So there you have it. From Napoleonic empire-building and battles in the deserts of Egypt and the Levant, to 1930s Art Deco on Kildare street. The ripples of History, as great events cause ripples arcing outward to cause a million small and distant effects.

Tracing these lines of influence and inheritance is certainly no science, but it does make for an enjoyable diversion.

There will be a new Hidden Dublin Quiz in the next week. If you enjoy the posts and quizzes please spread the word. I am going to begin a little business soon, a sort of walking tour and discussion group, for people who love history and old buildings. I hope some of you will be free to join me.

Sources:

Dublin 1660-1860, a Social and architectural history. Maurice Craig, 1952.

Napoleon , The Path to Power- Phillip Dwyer. Pub. Bloomsbury, 2007.

Web, general sources/fact, date-checking.

Archiseek.

Wikopedia.

Reblogged this on Arran Q Henderson and commented:

my favourite-ever post….

LikeLike

Very interesting post – Napoleon; a much maligned person, a bit like Cromwell (dare I say that to someone from Ireland ?) they both introduced new and enlightened thinking, which unfortunately gets forgotten in the need for the establishment to demonise them for political reasons.

Love the images accompanying this post.

David

LikeLike

Hi David,

delighted you enjoyed the post. In fact, well done just for getting through it all! – it is certainly longer than the average post, and covers quite a lot of ground. Fair play to you and thank you for taking the time to comment, that is always appreciated.

As regards Napoleon, I think it is such a mixed, and complex, (sometimes even contradictory) legacy, that scholars, historians and those of us who love history will be debating it for, well forever in fact!

He – N.B.- made so many extraordinary changes to Europe, sweeping aside so many old and ancient regiemes and introduced so much progress and so many reforms. On the other hand, one can not get away from the basic fact that he invaded countless countries, and waged a huge, global war that costs the lives of millions of people. Whatever you think of his reforming and modernizing zeal, he did kill a lot of people.

Nor was he exactly a democrat, although he deposed the church and old corrupt monarchs all over Europe, (and even further afield) he himself had highly autocratic and self-glorifying tendencies.

There is a core paradox here: about someone taking a democratic revolution and using it to transform themselves into an emperor, no? Having siad all that, there is still a huge, enormous amount to admire. I’m just glad i wasn’t an ordinary Spanish, French or Russian foot soldier when he was around!

As regards Cromwell, you’ve opened up such a huge can of worms there I’m not going to tacle that one right now! Maybe another day however.

I’ve done quite a bit of research on him and his record and legacy in Ireland, read various histories and 2-3 biographies, and questioned some of our leading experts.

I’ve tried to synthesize some of that acquired knowledge, about him, and my own reflections, here on this blog as best i can. Obviously it is an immensely complex subject, and still very, deeply contentious here, not least because of the huge, vast, dispossessions of land that took place after his conquest here. Whether he actually encouraged the killing of ordinary Irish civilians here, as is so often, routinely claimed here, is another matter.

If you are interested in the informed Irish perspective, may i direct or invite you to my posts on 17th C irish history? There are 2 or 3 of these, generally grouped among the “St Patrick’s Cathedral” posts.

Many thanks again for your thoughtful and considered reply, I am delighted you are enjoying the blog, As you know, I very much enjoyed your archeological investigations in the desert.

my very best regards- Arran. (Henderson)

LikeLike

Thank you for the detailed response to my (rather contentious) comment.

I shall certainly go and look through your blog for further historical items.

One thing I try, is to take great care and see a subject such as history, from as many points of view as I can find; it is unfortunately very easy to either view events from a modern prospective (always a bad idea) or let one’s prejudices get in the way.

Thanks for the kind words.

David.

LikeLike

My pleasure David, and i hope you’ll find the 17th C posts of some value. Like yourself, I also try and be as fair, accurate, and balanced as I can. Popular conceptions of history can indeed be a catalogue of cliche and received ideas, and you are quite right to question them.

Having said all that, I’d better warn you however, that unlike in the UK, where Cromwell is understandably viewed as someone who challenged absolutist monarchy and championed a parliamentary democracy, in Ireland his legacy is very, very different. Cliches and misunderstandings apart (and there are many) there’s still absolutely no doubt that his armies (particularly his son and law and sucessor-as commander here, Henry Ireton) destroyed crops on a huge scale, causing a famine and killed hundreds of thousands of people. To say nothing of the Penal Laws that followed- aimed at the majority Catholic population- and the mass dispossession of their lands. You won’t persuade many Irish people that Cromwell was a good guy or a good thing for Ireland, because the record simply doesn’t support such a view. But I’m delighted you’re going to read the posts in question. They are by no means comprehensive, still less definitive. But i hope they offer at least an introduction to the subject here in Ireland.

very best regards- Arran.

LikeLike

Thanks Arran,

I am looking through your blog at the moment and there is some fascinating stuff that will send me away looking for more.

I certainly don’t see Cromwell through rose tinted glasses hence the (?) when I made the comment.

A bit like 1916, Ireland has had a hard time of it.

Please be forgiving if I tread on some tender toes but… it is nice getting another point of view.

Unfortunately the internet can be a little unforgiving if one is not ‘very’ careful how things are phrased – no eye contact.

David.

LikeLike

[…] Other tours, available by request by advance booking. Early Modern Architecture in City Centre Dublin. Egyptian Details Tour. – From the national Concert Hall to the Library Annex: From to Egyptian- style neo-classicism to Egyptian-flavoured Deco. See here for a quick flavour of what this tour contains.. or, for much (Much) more detail and background historical detail on artistic infleunces, how they work, and what call the ripples of history effect, have a look when you have time, at this long but popular post. […]

LikeLike