Look at this. What do you see?

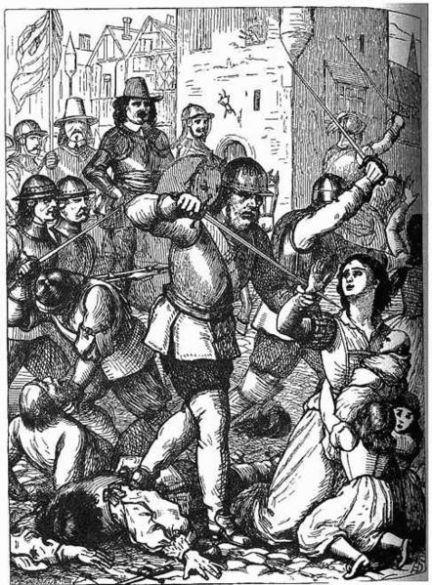

Above is a picture of an English soldier about to coldly run a sword through the throat of an Irish woman, as she, desperately, tries to protect her children. Look at his feet, you’ll see he also tramples on the body of an innocent civillian, already dead, while his colleague, just behind, smashes in the skull of an unarmed civilian. This depicts a scene from the siege of Drogheda, after the town fell to Cromwell’s troops. They certainly killed most of the garrison, but most Irish people believe they also slaughtered the civillian inhabitants too. Images like this resonate powerfully in the minds of many Irish people, to this very day.

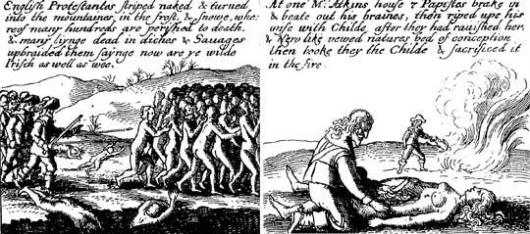

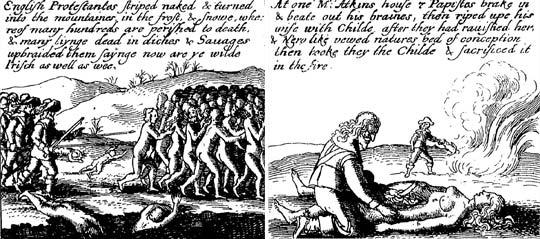

Below is another illustration, this time from a book of woodcuts published in London just a few years earlier. It depicts another scene, from 1641, several years before the siege of Drogheda, namely the proported massacre of thousandss of Protestant Scots and English “Planters” (settlers) in Ulster. Images like this also resonate powerfully with many Irish people. Although not exactly the same Irish people.

The first image comes from the Crowellian Conquest of Ireland following the Confederate wars here. Cromwell is the man on the horse. He was definitely not a good thing for Ireland. A large amount of people los their lands, others were exile soon after to the barren soil of the west, other deported,effectively as slave labour and by far worst of all, (and yet strangely the least remarked upon today) there was a horrific famine quite soon after his departure. Many Irish were killed during his campaign, although it is now a matter of fierce debate exactly how many civillians were deliberately killed. In the Republic of Ireland today however especially among the majority who come from a Catholic background, it’s almost an article of faith that Cromwell’s men slaughtered the civillians of Drogheda. I’m not a fan of Cromwell, but I’m not so sure either that they slaughtered civillians in that town.

Today we continue our leisurely progress around Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, using the old place as a sort of lens, through which to look at Irish history.

There’s nowhere better to examine Irish history, military history in particular. The cathedral is full of war memorials and soldiers’ tombs. It’s especially rich in artifacts from the complex, violent and bloody turmoil of the 17th century. That is the story we shall pick up again from our last post, and continue following today.

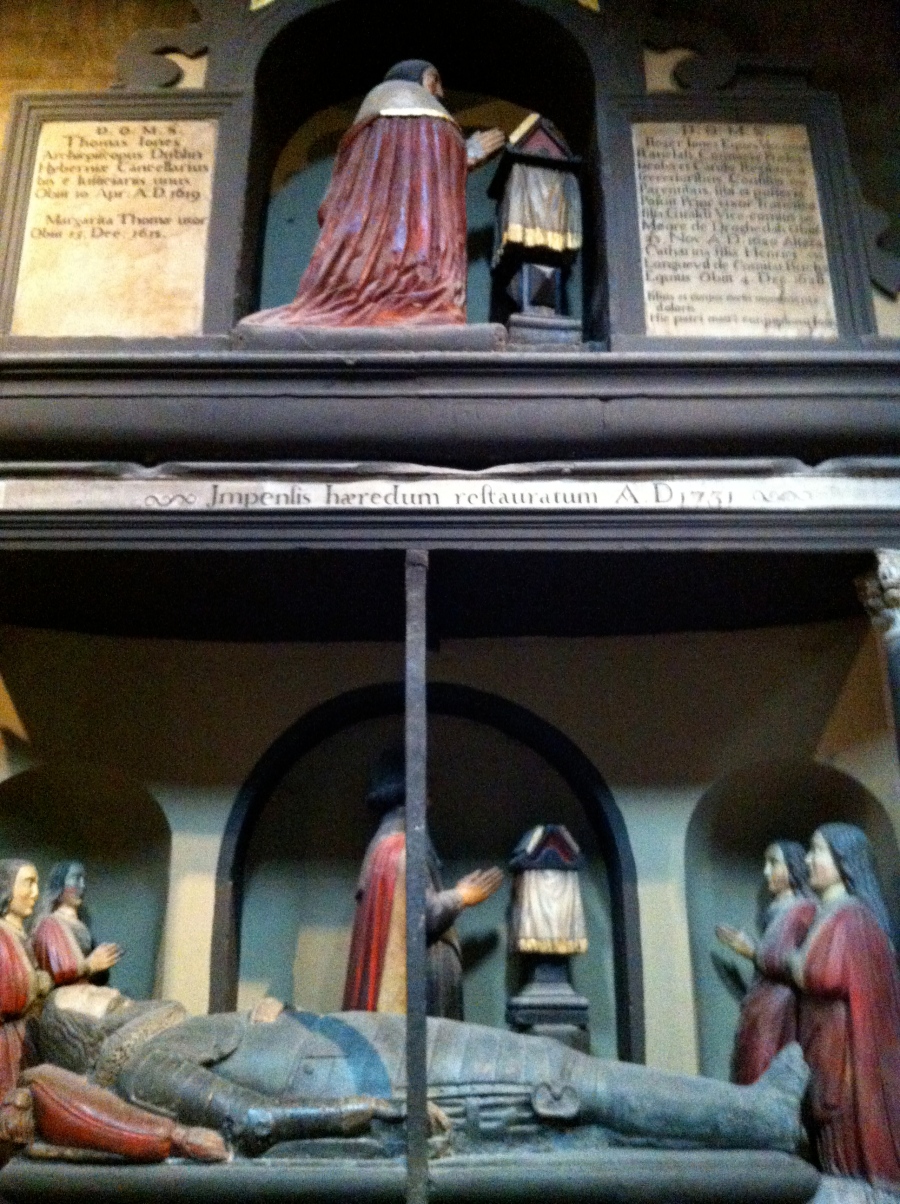

In that recent post, we focused on the Boyle memorial, dedicated to the earl of Cork, Richard Boyle, carved by Dublin sculptor Edmond Tingham. We used it to glance at events during Boyle’s lifetime, looking to the south of Ireland to the early plantations in Munster (including Walter Raleigh’s and Boyle’s own estates) across to London and politics and intrigue at the Elizabethan court, and northwards, to the plantations of Ulster.

As we saw, this last development prompted ferocious resistance from local people, led by the great Gaelic Lords, Hugh O’Neill and O’Donnell, who scored significant Irish victories in the early and middle years of that protracted conflict known as the Irish Nine Year war. But despite various humiliations, military defeats, setbacks and vast expense, all inflicted by O’Neill and his allies on the crown, the English did ultimately prevail, following victory over a Gaelic-Spanish coalition at the battle of Kinsale in 1601.

We left that story with the departure of O’Neill and O’Donnell as they sailed for exile in Spain. This was a momentous event in Irish history, signaling the beginning of the end for over a thousand years of proud, highly distinctive, independent Gaelic culture. The most formidable source of resistance had now been broken and the new generation of English was here to stay, as colonial administrators; soldiers, settlers, and merchants. Backed and favoured by the crown, with land grants and with access to modern technologies and capital, they were undoubtedly in the ascendant. But not everyone was prepare to give up and accept the plantations, as we shall see.

Because when we jumped forward 30-odd years, from the battle of Kinsale to event of the early 1640s, we saw or rather hinted at a new period of revolt, when Boyle temporarily lost lands to the Irish Rebellion of 1641. We know Boyle’s sons managed to recover his lands, but that is not even 1% of the story. So what was this rebellion, and what were its consequences? Today we shall find out.

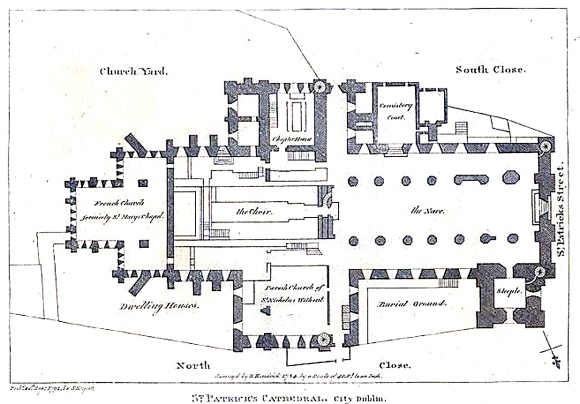

Today we remain again at the western end of the cathedral, but we cross the nave this time to the North wall.

As we cross we glance at the old Stone well head from the time of Saint Patrick himself, covered in our first “Origins” post.

Inevitably we also look down the full length of the aisle. In the atmospheric gloom, under the great vaulted ceiling, we can dimly make out distant, but wonderful things, details of pulpit and altar at the far end of the church, great heraldic flags hanging magically from splendid old choir stalls, a hint of winding stone stairs, monuments of great battles.

We are tempted to charge down and look at all these treasures. But if we do, we shall miss another wonderful artwork.

This large piece across the aisle (above) is dedicated to Archbishop Thomas Jones, depicted above, and to his son, Roger Jones, seen here kneeling in the lower tier. Thomas was archbishop of Dublin. But his Roger hails from the following generation. He was a general during the Confederate wars. Readers of the previous post might have already noticed the stylistic similarities to the Boyle memorial, and guessed, yes, this work is by the same sculptor, Edmund Tingham, of Chapellizod in Dublin. But readers from overseas might also be wondering what were the Confederate Wars.

We’ve already mentioned the Ulster Rebellion of 1641, also called the Irish Rebellion. We also saw Charles I (below) sacrifice the loyal Stafford under pressure to parliament.

Charles was, in truth, a pretty bad king. His French inspired, absolutist tendencies caused huge tensions with the Puritan-dominated Parliament in London, tensions that would ultimately provoke the English Civil war. But for all his failings, Charles was not a bigot. He appeared well disposed towards his catholic subjects. In contrast, the Puritan Parliament was by both instinct and religious conviction – deeply and instinctively hostile towards Catholicism. For that reason, prior to the outbreak of the Civil war, appeals by Irish Catholics to the king seemed to represent their best chance of redress on land and religious and civil liberties.

Charles may not have been a bigot. But unfortunately he proved cynical and opportunistic. With his expensive tastes constantly frustrated by the London parliament, the king soaked the Irish as a source of cash. Charles promised reforms and concessions, (concessions called “the Graces”) in return for large amounts of money, then failed to deliver his side of the bargain.

In the face of the Plantations, of continued non-action from Charles and hostility from parliament, and with both those English parties distracted and weakened by political wrangling, some of the remaining Catholic elite in Ulster seized the opportunity to try and force the king’s hand.

In that year of 1641, they gathered men and arms together as a show of strength, by staging a strange sort of rebellion. It was a strange one because they dressed this defiance up, addressed to both king and Parliament, as a show of loyalty, claiming they were protecting Charles from his enemies in Parliament. They even carried a letter (albeit probably forged) to show they had the king’s blessing. But there was a clear, implied threat to both crown and parliament, if concessions were not now delivered.

We will never know how England would have reacted to this initially rather civilized, highly stage-managed event because the Irish leaders then lost control of their men. After years of land confiscations and other humiliations, feelings among the ordinary people were running high. Events quickly span out of control as many went on a rampage against local Protestant settlers in Ulster. There was, in short, a massacre.

This terrible event was to have extreme, horrific consequences over the next months, years and indeed ultimately, for centuries of Irish history.

The numbers of people killed were greatly exaggerated after the war that followed. Protestant propaganda claimed women and children had been drowned, decapitated, impaled on pikes, cut open, burnt alive and every other conceivable form of barbarity. Books were brought out, with woodprints graphically illustrating the savagery of the Irish. It was claimed a hundred thousand had been slaughtered, a ludicrous assertion, since there were not that many protestants in the whole of Ireland. Nonetheless, there’s absolutely no doubt several thousand civilians were killed. This was an event that would live long in the memory, and serve to justify much horror yet to come.

To read about the conclusion of the Confederate Wars and the arrival of Cromwell, please visit the next post.

Arran, I was vexed by that new media uploader as well. I discovered that by going into the stats page and then going to “my blogs,” THEN clicking on the title of the blog……going through that tunnel seemed to work for me. Mind you, I could have that a little backward as I just “found” it by accident and trial and error. The new uploader is a pill! Thanks for the post! 😀

LikeLike

Thanks Angela, you are totally right about the new uploader, a pill is the right word for it! But you still steered me the right way, back through posts, then edit then, finally, I saw the tiny drop down option button to resize the images. Good steer, thanks a million. Really glad you read and enjoyed, you’re too kind as always. Have a super Christmas.

LikeLike

OH and Merry Christmas!

LikeLike

Great post Arran. I look forward to the continuation in the new year. have a good Christmas.

LikeLike

Thanks very much Dermot, and you too.

LikeLike

Great post. I’m enjoying this history. Have a Merry Christmas.

LikeLike

Thanks very much MF. I’m not entirely happy with this, or the next post, so I’m relieved and really glad a few of my readers are saying they enjoyed it/them. Very grateful for the feedback, today even more than usual!

LikeLike

Apologies for being tardy in reading this and your next post! I enjoyed it, even if you aren’t entirely happy with it. I have relatives from Drogheda; they aren’t keen on Cromwell at all, as you can imagine. Most of what I’ve studied on Charles I and Cromwell have been from British sources, so I do appreciate reading an Irish perspective.

LikeLike

This is going to take me a while, but from an English point of view (Sweep aside the propaganda which is not to say it isn’t important) but it all comes down to Catholics and the Spanish…..

David.

LikeLike

It’s absolutely true to say that it was a central part of english foreign policy in this era to avoid catholic encirclement by france, and especially spain and Ireland, acting in concert. However it’s all a bit chicken and egg. The Irish would not necessarily have had any need to ally with the Spanish (and much later, notably in 1796-78) with the French) if their lands and rights had not been taken away. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that catholic nobles were happy to be loyal subjects, if they had not constantly been humiliated and denied a fair crack of the whip. The prime example of course – from the Elizabethan era- is the great O’Neill and the 9-Years War. From an english viewpoint he might look ungrateful, two-faced and treacherous. But that view completely neglects what was happening to his kinsmen and their lands and rights across the wider ulster scene.

LikeLike