I recently posted on an event that runs in Dublin November each year called Open House, dedicated to architecture by helping to educate and inform us all about the history and practice of that great art, and by giving the public access to some of the best buildings in the country.

It’s one of my favourite weekends of the year, so always I try to cram in as much as possible. Anyone who read that last post will have seen a little photo- essay of the Pearse Street area. Well, later the same day my friend and I crossed over the nearby river Liffey, to catch the last 40 minutes access, to James Gandon’s mighty Customs House.

Gandon (1743-1823) was born in in London, the son of a gunsmith of Huguenot ancestry. He studied at an academy of drawing. Later he had the noticeable talent and excellent fortune to be apprenticed to the great William Chambers.

Chambers was arguably the leading London practitioner of his time. He was architect to the king, tutor to the Prince of Wales; the designer of Buckingham Place and of the lovely Summerset House on Piccadilly. Although Chambers never so much as set foot in Ireland, he was nevertheless also architect of at least one superb building here- namely Charlemont House and one unmitigated masterpiece: the mysterious and dazzling Casino at Marino.

Anyone who knows any of these great works, in London or Dublin, will recognize that Chambers was a master of the neo-classical style. There’s little doubt the young James Gandon absorbed much from these years. Perhaps the promising young architect was now looking forward to a comfortable life, designing the stately homes of England. He was already much in demand, even the subject of invitations from the imperial Tzarist Russian family, the Romanov family, to get him to go to Saint Petersburg and work there. Fate however, had other plans for Gandon.

above, portrait of James Gandon. Look and see, what building is in the far distant background? Yes, of all his wonderful buildings, this was his masterpiece.

above, portrait of James Gandon. Look and see, what building is in the far distant background? Yes, of all his wonderful buildings, this was his masterpiece.

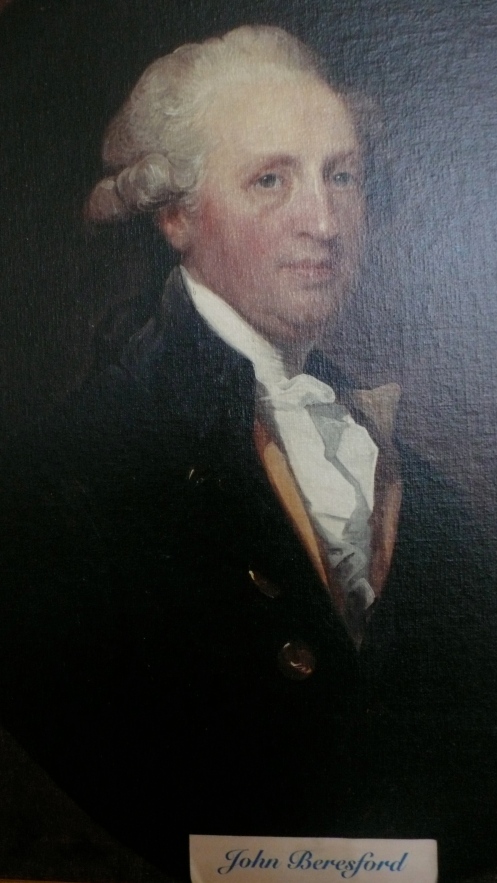

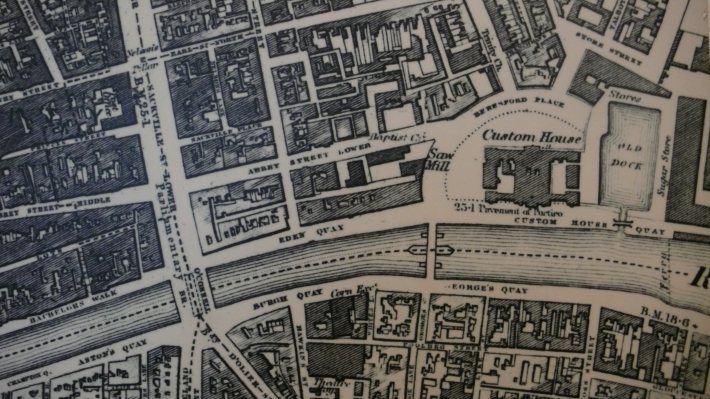

Over in Dublin, strange events were afoot. A group of powerful men, led by the especially formidable John Beresford (1738-1805) had an idea. They had decided they were going to remove the ancient Customs House, from the old traditional mercantile centre of Dublin around Christ Church and Temple Bar, moving it much further east, near the mouth of the port.

They were faced with stiff opposition- and not a little outrage- by a powerful coalition of leading merchants and traders, all of course had their offices and warehouses in the old centre and whose business would be seriously disrupted and discommoded, or worse, by the proposed move.

These merchants, and Dublin Corporation (which they dominated) now fiercely resisted the new project. They may have been a special interest or “special pleading” group but they also had a point. Beresford’s idea was going to cost a fortune, (which would of course come out of duties and taxation). Besides which, the new site chosen was extremely unsuitable, as it was basically a swampy marsh.

As if all this was not enough, there was a nasty whiff of suspicion surrounding the proposal. The land selected for the new construction and the land all around the new site was owned by the Gardener family. If the new Customs house was located here, that land could only rocket in demand and in value. There was much talk of corruption and nepotism.

Because, by an extraordinary coincidence, Luke Gardiner’s sister was married to…John Beresford. The two men were brothers-in-law!

No caption necessary. The behemoth of late 18tn century Irish power politics.

Opposition was so politicized, and so heated, that when work did begin, in 1781, a large mob numbering several thousand gathered to try destroy the initial foundation works. Then they tried to burn the construction site to the ground!

Beresford however was made of strong stuff. He was one of the most powerful men in Ireland. He had formidable family connections (his brother was the Marquis of Waterford, for example and John’s own second wife in particular also came from wealthy and powerful landowning interests. These connections, as well as his own abilities, had helped him acquire the immensely important role of the king’s chief collector of taxes in Ireland. Once in this position Beresford wielded even more immense clout and influence. Almost all the commercial revenue of the island passed through his hands and under his beady-eyed scrutiny. Visitors to Dublin were taken aback and often remarked on his mighty station and the sheer dominance of Beresford family in Irish affairs. In fact, the phrase “an uncrowned king” was employed, on more than one occasion.

In the general scheme of things, Beresford record and legacy would be, at the very least, disputed today. For example he later supported the Act of Union, never a favourite position with patriots. On the other hand, although this was certainly not Beresford’s reason for his support for the Act, somewhat paradoxically that change of 1801 and the subsequent move if Irish parliamentarians to Dublin probably helped pass catholic emancipation in Ireland. (This is one reason why the ultimate genius of Irish politics, Edmund Burke, supported the move)

Beresford saw off at least one Lord Lieutenant who tried to remove him. This was the Earl Fitzwilliam, appointed under Pitt’s Government. Fitzwilliam was so alarmed by the Beresford family’s overwhelming power in Ireland he tried to replace John as Revenue Commissioner. However, Fitzwilliam appears to have then been abandoned by Pitt, when Beresford fought back. Fitzwilliam was himself undermined, while John was soon restored to all his offices and positions in Dublin.

Besides all this, Beresford was also head of the powerful “Ballast Committee” a vitally important body dedicated to stopping Dublin Port silting up, mostly through the design and commission of huge engineering works (such as the South Bull Walls and later the North Bull Wall, either side of Dublin Bay)

Beresford’s sheer bloody mindedness drove the Custom’s House project through. It is entirely possible he and his in-laws made unsuitable profits from the transaction. (That would make it an almost unique first as an example of corruption in Irish planning and re-zoning history, not)

However, whatever the whiff of graft and ill-gotten gains, the creators of the Customs House were at least partially exonerated by history, for two important reasons. Firstly, the bay and river do silt up. The Customs House did therefore indeed need to move eastwards. As ships got ever bigger, the old arrangements made less and less sense. (Indeed even the new Customs function later had to move even further eastwards and seawards and the new building assumed other state functions)

The second reason is the young architect Beresford had found and brought over from London, to design and oversee the huge new building. That man was of course James Gandon. Whatever the shady political and financial background to the Customs House development, the movers and shakers behind the deal – through their recruitment and appointment of Gandon – could at least be confident their new building would very likely boast genuine artistic distinction.

detail of the facade, and one of the river Gods (Anna Livia in this case) Incidentally, the balloon you see is from the Open House team. You can see them all over the city this weekend each year. It’s a nice device to signal the event and flag the “Open House status of the many open sites during this great weekend.

In the event, his achievements would surpass even their ambitions. Because the building, the first of four great Georgian-era, set-piece building James Gandon would go on to design in Dublin is- like the others- a masterpiece.

The furry surrounding the project was so intense that stories say that in 1881 Gandon had to be smuggled incognito into Ireland on a sailing ship, with both his name and his new job here a closely guarded secret.

The results proved worth it. His exterior is extraordinary. The huge central space is capped by the green copper dome you saw above. But everywhere here you look is spectacle and grander.

above, note the frieze in the pediment with Neptune as the sea with the female allegorical figures of Britannia, and her sister kingdom Hibernia. Note also the the larger, free-standing allegorical figures higher up, depicting values like peace and prosperity.

above: the Lion and the Unicorn, a typically loud protestation of loyalty by the Ascendency class of the times.

The decorative scheme is especially interesting. Gandon was a visionary, but he was of course also merely the head of a talented team of individuals, including Irish master mason Henry Darley and the sculptor Edward Symth. The stonework is thus decorated with an amazing quality of carving, many in low relief, such as these bulls’ heads. (such as this one below, seen just below the corner of the pediment)

They refer to the importance in both live cattle and in beef exports to Ireland economy. In between the bulls’ heads, instead of the conventional Greco-Roman style garlands of flowers, the decorative stone carved “swags” are instead depicted as the hides of cattle, as leather export was also vital to Irish trade.

In these ways, the building is a curious but very successful fusion of harmonious neo-classical learning with contemporary, location and function related cultural and commercial references that allude to the purpose and role of the building, what would today perhaps be called “site-specific” sculpture. This was after all a customs house, so everywhere you look are allusions to trade and export and commerce, and more generally, to the sea, which bore that trade.

above, detail of mythical sea creatures, flanking Neptune’s trident.

One of the most celebrated aspects of the designs of the stone decoration are Symth’s wonderful carvings of allegorical river gods, depicting Ireland most important rivers, such as the Shannon, the Barrow, the Lee, the Boyne, Liffey and so on, also vital for trade and navigation.

above and below: same details, focusing on two of Symth’s river gods.

The river gods are nearly all male. Only the Liffey, in keeping with Irish traditional depictions is personified as a female character, “Anna Livia” – above.

The project took over 10 years to deliver. Superb artists, craftspeople and artisans, working hard, at the top of their game, do not tend to come cheap. Predictably, none of this was delivered as a bargain. (Beresford’s adversaries were right on that score at least. ) The final bill for the Customs House was something like at least £200,000, a whopping, breathtaking, astronomical sum for that era. It’s even possible, as certain reports maintain. that the true final sum may have been even higher, up to £600,000, when all the finishes, art works and furnishing were included. Either way, when the figures are by time adjusted to real values, then by square footage, this is one of the most expensive buildings ever made in Europe.

On the, ahem, positive side, it was generally acclaimed to be one of the finest in Europe. Now, and not for the last time, Dublin, the capital of a small peripheral nation, was making buildings on the scale and grandeur of London or Rome, on the scale not of a provincial centre, but of an imperial capital. Whether that is inspirational, or simply delusional, is a matter of personal opinion! Personally, I’ve always tended towards the later view.

above, The Customs House as one of the marvels of Dublin, in this 19th Century postcard, reproduced courtesy of “Come Here to Me” blog.

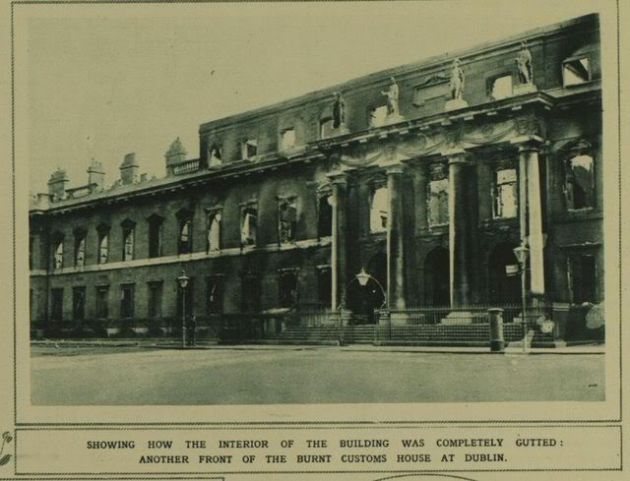

Tragically, the interior of the building, like the GPO and Gandon’s own Four Courts were later destroyed by the political violence that erupted in Ireland between 1916 and 1922, as the Easter rising, the War of Independence, then finally the Irish Civil War, convulsed the country in rapid and lethal succession.

The GPO was destroyed in Eater 1916, by shells fired from a British gunboat; while of Gandon’s two great riverfront buildings, the Customs House was destroyed in the War of Independence and the Four Courts, (and precious historic documents within) in the Civil War. This last two tragedy also led to an appalling loss of thousands of important historic documents, as the Irish public records office was housed in the Four Courts, a thousand years’ worth of irreplaceable historical sources were lost forever in a blazing explosion, with many suspecting the destruction was deliberately orchestrated out of spite, by the occupying anti-Treaty forces.

At the Customs House, a year or so before, the fighting and terrible fire resulted in the entire interior being destroyed. As the building blazed away, on the 25th of May, 1921, the huge dome came crashing down, being shattered beyond repair.

The more moderate, pro-treaty side won the Irish war. But they inherited a badly divided country, now smaller as it was officially partitioned, (via the creation of Northern Ireland) and a devastated infrastructure. The Customs House building, once the pride of the city, now lay in a smoldering pile of smoking rubble.

For a poor, newly born, independent state like Ireland, with extremely limited finances, the new Free-State government might have been forgiven for prioritizing other issues. To their immense, ever-lasting credit however, the decision was made to restore, if necessary to entirely rebuild, all of Dublin’s devastated great public buildings.

In the case of the Customs House that happy announcement was tempered by the grim knowledge that the previously stunning interior, with its beautiful fittings, was entirely, definitely destroyed.

above: as this picture makes painfully clear, the Customs House was almost entirely obliterated by the horrific fire of May 1921. The dome and cupola, most of the facade and all the the interior were completely destroyed. Only fragments of the facade remain standing, like a stage set, giving the illusion the building was in any way intact.

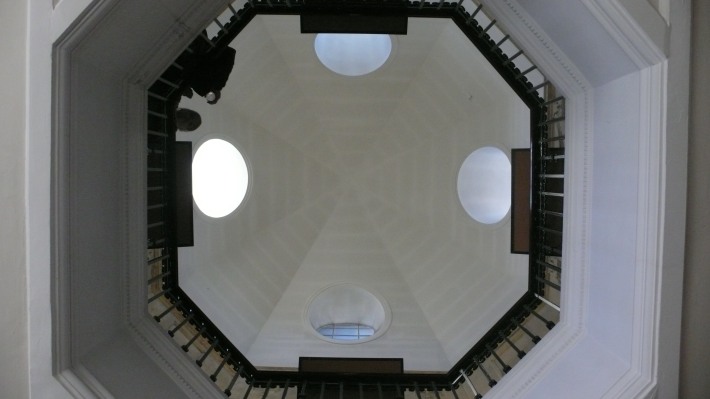

Rebuilding the entire vast edifice, with all it hundreds of offices, at the same quality and using the materials of the Georgian era, would simply have been prohibitive. So a compromise was reached, whereby the exterior, including the stone façade and dome, and the public areas in the immediate interior of the building, would be restored as close as possible to Gandon’s creation.

The office areas further back however, out of the public eye, would simply be made usable again for use by the civil service, but not in any manner of Georgian splendor. And so it is today. The Customs House is once again beautiful on the outside, and in the immediate public areas where we enter. The upstairs, with its restored octagon skylight below the great dome, has been rebuilt for example.

So too have some of the first floor reception rooms. On the day we visited, somebody, perhaps the Open House organizers, perhaps the excellent OPW, had gone to a lot of time and trouble to showcase a very good set of displays on the building and the key protagonists involved. Here you see James Gandon’s original drawing desk.

So today, while the Customs House boasts a superb facade, that is all it is. Further back, just hidden out of sight, the building is nowhere near as grand, but rather dreary, utilitarian sort of place. Its appearance in this sense is something of a sham; a mere pretense at former glory and grandeur. It is today, as our rather rude Irish expression goes: – “all fur coat, and no knickers”

Well, maybe the public lobby areas are some form of knickers. (I can’t believe I am choosing to extend this ridiculous metaphor) And as for Gandon’s stunning façade, it may be a coat.

But reborn and rebuilt, what a coat it still remains.

Excellent post, Arran. I really enjoyed it and I will pay far more attention to the Customs House in fiture.

LikeLike

many thanks Dermot. We’re very lucky to have this Open House event in Dublin (in cities all over the country now I think) – it’s such a great way to get access to these buildings and all the stories behind them. Haven’t been on your blog for a while, very remiss as I always enjoy your excellent posts. About to put that right now. -A.

LikeLike

Wonderful source of information and superb photos 🙂 Maire

LikeLike

I agree, especially with Eikenlaan — the accompanying photos and your commentary are superb. I wish we’d squeezed in more time to visit the Custom House last year. We spent more time at Trinity and the Guinness factory … like all the other tourists! The river god symbolism is wonderful — thanks for that, and for the political backstory surrounding such an important building.

LikeLike

Hi, yes, Trinity is a wonderful collection of buildings, but i always get a little frustrated when so many visitors (and so many of my students, alas!) get sucked into the great advertising tourist trap that is the Guinness storehouse. It has some interesting displays of transport & social history, but ultimately it’s basically an enormous 3-dimensional advert! Many of the same visitors don’t make it to Glasnevin Cemetery or to Kilmanham Gaol, which is a real shame I think, so much more interesting and full of real history. But i am sure you had a good time anyhow but it sounds like you are really interested in history and culture, so let me know if you ever come back to Dublin, & I’d happily send you a suggested itinerary! Many thanks for your generous comments also, they are greatly appreciated. -Arran.

LikeLike

I’ll definitely ask you for an itinerary on our next visit. Hopefully it won’t be too long before we do. If you’ve got anything forthcoming about the Book of Kells (er, actually, the Page of Kells, since all we saw was just one page of it), let me know!

LikeLike

Fabulous post as ever Arran. I really would love to visit Dublin and your posts make me want to visit alll the more..

LikeLike

aw shucks. you say all the right things – I am purring away here, like a small and happy cat.

Flattery will get you everywhere.

LikeLike

Customs houses and other government buildings here (U.S.) are much the same – lovely facade and typical dreary working area elsewhere.

Wonderfully detail article. Great pic’s. Enjoyed.

LikeLike

Many thanks Jamie, really delighted when people enjoy and take the time to say so, it is much appreciated. very best regards- Arran.

LikeLike

This is a fascinating history with great photos! The Beresford and Gardener Custom House saga would make a great television series.

LikeLike

hey thanks Catherine. Yes, I agree with you, it actually would make for a good TV show, with all the scheming families, and the rivalries and intrigues. Maybe I should have a crack myself. But I don’t think our national broadcaster would be that interested in commissioning it- most of the key characters came from the ascendency & the unionist persuasion – not always viewed with great interest or sympathy in modern, independent Ireland today! Delighted you enjoyed it though, it was a fun story to tell. Thanks a million for your visits and encouragement. 🙂 A.

LikeLike

Fascinating detail and a wonderful tour, through all the trials and tribulations,thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you Patti, thank you very much. Really pleased you enjoyed it. Delighted. 🙂 Thanks for taking the time to comment, makes a difference. Regards from Dublin – Arran.

LikeLike

I love how you tell the story (history) in such an interesting way. learning more about Ireland with your every post. there is so much info in this one and they are wonderful. 😀

LikeLike

Hi great article, There is new information coming to light that the building was in bad repair & there was timber props inside hence they helped it burn to the ground.

LikeLike

Thanks Gary. good spot on my error, thanks have put that right now. That’s also interesting about the timber and structural situation prior to the fire. Delighted you enjoyed the piece. Many thanks for taking the time to comment. -Arran.

LikeLike

Very interesting article about the Customs House which is told in quite a thought provoking way.

LikeLike

Delighted you enjoyed, many thanks Tim for taking the time to say so. It’s always very nice to get feedback. -Arran.

LikeLike