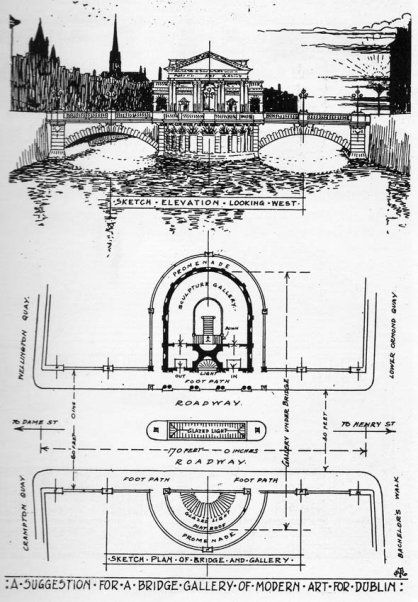

Recently, we asked readers to identify what this drawing below was, and why it was never built.

Many of you wrote in to say, very correctly it was Edwin Luytens’ design (one of at least two he did) in the 1900s, for the art collector and gallerist Hugh Lane.

(Above: Hugh Lane, painted by John Singer Sargent, image courtesy Wiki Commons)

Many of our Irish readers will know most if not all of this tale. But for anyone who likes a recap, and for those overseas, here below is the whole, sorry story.

Hugh Lane (1875-1915) . later knighted Sir Hugh Lane, was of Anglo-Irish extraction. He was born in County Cork but grew up in in England, mostly Cornwall.

He did however maintain strong and loyal links with Ireland, throughout his short but extraordinary life, spending a lot of time, especially summers, in Ireland, in Dublin, and at in his famous aunt’s house near Gort in County Galway.

Lane later became a very successful and forward-looking art collector, and art dealer. He was based at first primarily in London, but with strong links to France and personal connections to the surviving French Impressionist painters.

His aunt in Ireland was the formidable figure of Lady Gregory, of Coole Park, County Galway, the writer, patron and co-founder of the Abbey Theatre.

Through her, Lane had met people like WB Yeats, Edward Martyn, and other leading members of the Gaelic Revival, nurturing the Renaissance in Irish Arts, crafts, language and literature.

As he became a successful art dealer Hugh Lane did his best in turn, using his connections, wealth and contacts to promote Irish painters and artists abroad.

He also took cultural exchange in the other direction, bringing international and continental art over to Ireland. In 1902 he mounted an exhibition of Old master paintings in the Royal Hibernian Academy. He also commissioned first John B Yeats (father of WB and J B Yeats) to paint a series of portraits of contemporary figures of that time, a series later continued by William Orpen and a vital record of Ireland and a legacy to Lane on its own.

But Lane would go further. Over time, he became convinced the Irish public should be able to see the best of European and International art. Amid strikes, war, poverty and everything else, Lane, counter-intuitively perhaps, determined what Dublin needed was its own, dedicated Modern Art Museum, to compliment the historical works in the National Gallery.

From that point onwards he worked to this end. He organized and as well as contributing his own money, time and energy was busy lobbying and fundraising. Crucially he lent, and later donated, large numbers of very high-quality pieces from his own collection, including works by Monet, Manet, Renoir, Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Edouard Degas, Rodin and others.

above: by Pissarro, and Top, Manet (Musique aux Tulleries). Below, Berthe Morisot.

Bluntly, if Lane had not done so at the time, we the Irish people would never have such valuable works in this country. Other priorities, plus sky-high prices in the international art market would have seen to that, permanently.

Having donated these beautiful pictures, Lane next lobbied Dublin Corporation (as they were then) to provide a permanent and fitting home for the collection.

In 1907, the Corporation accordingly provided a premises on Harcourt Street, called Clonmel House. (ahrd by the entrance to the Ivegh gardens) But Lane considered this house inadequate and unsuited. By 1912, he was threatening to withdraw his collection.

What Lane really wanted, his dream in fact, was that his collection would move into a new, purpose-built gallery. To this end he now consulted and commissioned the legendary Edwardian architect Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Many will be familiar with Lutyens’ works in Ireland. These include the beautiful War Memorial Gardens; to fallen Irish soldiers of the First World War, at Islandbridge, (along the Liffey and to west of the city) ; as well as Lambay House on Lambay Island in the Irish Sea, off Howth head; and Renvyle House in Connemara.

Internationally, much of his finest work is in England as you’d expect, but- most spectacularly- in India.

Indeed Lutyens was the architect of the Edwardian late empire period. He designed Connaught Place, the government and administrative centre of India in New Delhi, including the Parliament, which is still in use today.

In any case, for Lane’s proposed gallery, Lutyens drew up at least two designs that I’ve seen. One would have stood at a corner of Saint Stephen’s Green. Frustratingly, I have not been able to find a reproduction of this online to show you here, which is a pain, even though I have seen the drawing in the flesh at least once, albeit a long time ago. if anyone can provide, a reproduction of the Stephen’s Green Gallery proposal, naturalluy I’d be grateful natural.

In any case, this Stepehsn green gallery plan was frustrated in any end. My fellow blogger, the writer and architectural historian Robert O’Byrne has written an excellent book about Hugh Lane, – According to Robert on his blog “the Irish Aesthete” – the Saint Stephen’s Green gallery plan was vetoed by Lord Ardilaun, the prior owner of the land.

Lord Ardilaun, a member of the Guinness family, had laid out and then given over the Green to the city, as a public park, way back in 1888 but the terms of the transfer meant he retained the right of veto (for any propsed changes) during the remainder of his lifetime. Clearly it seems Lord Ardilaun didn’t want any buildings on his park, not even at the corners, not even if they were designed by legendary architects and not even if stuffed full of priceless French impressionist painting.

“My park: my rules” – he probably groused to himself in the mirror. The plan was scotched.

You might think, after this setback, that Lane and Lutyens would go back to the drawing board (literally) and come up with an alternative plan. Something sensible; something modest; realistic. You would be wrong. Such is not in the nature of strong-willed creative people. Not in the nature of genius at all.

Lutyens’ second, startling, wonderful design featured a covered bridge, spanning the river Liffey around the site of the famous Ha’penny Bridge.

Yes, with the gallery inside the bridge. Here you go.. have another look.

I haven’t seen this drawing in the flesh for a few years now, but my recollection is that the rendering, the drawing, is by Lutyens himself. Whatever you think of the idea, you’ll allow it’s a stunning and sensitive piece of draughtsmanship.

Bizarely, it is not the only design for the Gallery bridge. here is another, by one Horace T O’Rourke (both images courtesy of the wonderful website Archiseek). Also pretty fabulous I think. In theory at least.

Although a wonderful concept, it is hard to say how practical,or even desirable a gallery in a bridge would have been in practice. For one thing, the bridge-galley, although in itself very beautiful, would have blocked the views down the Liffey.

It also would have necessitated the demolition, or at least a move, of the Ha’penny bridge, an icon, almost the emblem really of Dublin as a city.

The bridge plan immediately faced stiff opposition, notably from the powerful figure of William Martyn Murphy, industrialist, tram owner, newspaper magnate, and leader of the Dublin business community and their interests. Murphy, who controlled the Tram company and several newspapers is still a controversial figure to this day for his role as a strike and union breaker in the Great Dublin Lock Out of 1913, (centenary this year).

He campaigned vigorously against Lane’s Modern Art Gallery through his newspapers and using his considerable business clout Other opponents claimed the bridge was too impractical, too expensive, or that damp rising up from the river would ruin the paintings inside. Others pointed out, not unreasonably, that with Dublin’s slums and chronic shortage of decent housing for human beings, an expensive gallery for modern art was a luxury Dublin simply couldn’t afford.

As the debate grew heated, even personal. Public figures took sides. Naturally many of the cultural elite, including Lane’s personal friends like WB Yeats and, of course his aunt Lady Gregory took his side. When the fuming Yeats wrote his famous, angry poem, familiar to every Irish school leaver, September 1913, starting with the immortal words, lambasting what he saw as Dublin merchants lack of taste, purpose or vision, he was referring directly to this gallery controversy…

What need you, being come to sense,

But fumble in a greasy till

And add the halfpence to the pence

And prayer to shivering prayer, until

You have dried the marrow from the bone;

For men were born to pray and save;

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.

above: WB Yeats. Angry and scornful poet.

But Lane, even with Yeats and other allies faced an unbeatable opposition. It was not only business leaders like Murphy who poured copious scorn on the proposal. Prominent nationalist Arthur Griffith stated the gallery was extravagant folly, or felt it was somehow not, (I’m paraphrasing here)- “not Irish enough”.

Irish patriot and Sinn Fein President Arthur Griffith.

No new gallery building was ever built.

Because the city had failed to provide a proper home for his admittedly, very special and generous gift of beautiful and expensive paintings, Lane now suffered a gigantic fit of pique and withdrew them. He even bequeathed them to England. But later, remorsefully perhaps, he added a codicil to his will, contradicting this last command, the change of heart made in his own handwriting and signed in three places. But crucially, Lane did this alone, the codicil was not witnessed, a simple oversight that would have enormous future ramifications.

Despite his huffiness about the modern gallery, Lane continued to work for the visual arts in Ireland. In January 1914, he was appointed director of the National Gallery of Ireland. Here he donated six precious old master paintings to that institution. They reside there to this day. If you walk the National Gallery, glance sometimes at the frames as well as the paintings, you will often see some interesting names like Lane, and George Bernard Shaw). Lane also worked in his new role at the National Gallery without pay, donating the salary money to a fund to purchase more pictures. But tragically, Lane never got to see a modern art gallery open, or at least never in the form or shape he yearned for.

He was killed in April 1915, aged only 40 years old. The ship he was traveling on from New York back to these islands, the Lusitania, was torpedoed by a German U-Boat. It sank in the ocean by Kinsale, off County Cork, very near Lane’s own birthplace as it happened. – with a catastrophic loss of life.

The Sinking, by U-Boat torpedo, of the Lusitania, Contemporary rendering, artist now unknown.

Many of the passengers, the victims, were Americans. This terrible sinking was one of the events that brought the United States closer to entering the First World War.

After Lane’s tragic death, and despite his handwritten codicil, his valuable paintings now became the subject of along-running dispute between Dublin and London. London said Hugh Lane had left them to London in his last final will. Dublin pointed out he’d spent most of his adult life passionately working to bring a modern art gallery to Dublin. Indeed he’d reconciled his original will with the handwritten codicil, in accordance with that clear wish.

Eventually a compromise was reached. London maintains legal ownership, which is vexing, but at least today Dublin has most, 31 of the 39 pictures on a on-going loan. The others eight pictures, the most famous eight if you like, rotate between the two cities, also on a loan system

There is something of a happy end to this sad story, albeit years later. Nearly twenty years later in fact.

In 1933, the wonderful Charlemont House, on the North side of Parnell (formerly Rutland) Square became available.

Although it is a 18th century town house, it is in fact a very fitting home for Lane’s pictures, because it was built for James Caufield, earl of Charlemont, the finest, most discerning collector and patron of his own age. There is no doubt that James built this townhouse with the display of his fantastic library and art collection in mind.

The place is bathed in beautiful light. The designer was no other than William Chambers, architect to the king, designer of Sommerset House, the home of the Royal Academy on Picidilly, and who also remodeled Buckingham Palace. In Ireland Chamers is responsible for the Chapel and the “Theatre” (the exam hall) in the Front Square of Trinity College, as well as the stunning Casino at Marino. His Charlemont House on Parnell Square is a something of a masterpiece.

The tale of James Caufield and the two extraordinary houses he commissioned in Dublin, make a remarkable thread itself. But let us save that story, for another day. I just like to think that Hugh Lane would have been pleased with this remarkable home for his amazing paintings.

If you have enjoyed the piece above, please leave a comment if you’d like. I always love to hear from readers. Thank you for reading.

Hugh Lane, 1909.

Sources:

Archiseek;

The Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery website and catalogue on-line;

The National Gallery website;

The Irish Aesthete; by Robert O’Byrne’s, especially his recent commemoration post on the 90th anniversary of Lane death, and his other post, on the portrait series commissioned by Lane, see these two links respectively: 90th anniversary of Lane’s death. and: Portrait series commissioned by Lane.

Where can I get an abridged version of this post? I’d love to sit down and read it, but me ereader restricts me to no more than 1000 pages per book? Be sure to let me know, and keep up the good work Arran!

LikeLike

Yeats poem conveys the scenario it adds an landscape to the history of the collection, great

LikeLike

Thanks. Great read. Have spent many happy hours in the Hugh Lane Gallery. It’s a fitting testament to such a visionary man. Sadly today a similar small-mindedness in relation to visionary projects for the city is very much in evidence.

LikeLike

How sad that he died on Lusitania.

Regarding Lusitania bringing the US into WWI – textbooks make a pretty big deal about that over here and disagree, but I’ll spare you and not go into that. 😉

Interesting post, enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Thank J.G. Delighted you enjoyed. We are always taught here the Lusitannia is more or less what brought the US into WWI, but I will definitely bow to your (far) superior knowledge on such matter. 🙂

Really glad you enjoyed the piece. Thanks for taking the time to comment.

LikeLike

Fascinating. The gallery on a bridge design was a curious idea.

LikeLike

Yes, indeed. Not sure it would have been the best thing for Dublin in general. But on its own merits it would have looked extraordinary. Thanks for your visit and comment:) Arran.

LikeLike