Old maps of Dublin: Viking & Medieval Dublin to the early modern era. 1,200 years of change.

The image below is the first known image of Ireland. It was drawn as part of a larger map, around 200AD, by the legendary Ptolemy, often called the Father of Geography. Culturally speaking, Ptolemy was Greek, but he was born and lived in Alexandria in Egypt, which by his era had fallen under Roman rule.

As a Dubliner, it’s very tempting for me to suppose or imagine the name “Eblana” -appearing on the east coast of Ptolemy’s Ireland- represents my own city. But no, sadly Eblana is almost certainly not Dublin. (Sniff). Dublin, as city at least, simply did not exist in 200AD. Modern scholarship suggests that Eblana may instead well be Loughskinny, now a small town further north (in the Fingal area) since this was an important and attested trading post in Roman times. But nobody knows for certain.

Although Dublin wouldn’t be a city until the mid-800s, there were almost certainly people living around the Liffey valley area, well prior to the arrival Christianity, from around 430AD, thanks in large part to you-know-who.

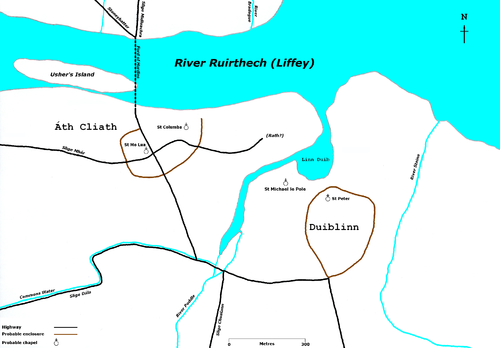

Most famously in the pre-Christain era, there was the Atha Cliath, “the Ford of the Hurdles” at a narrow points in the river Liffey, an important nexus which would have acted as a draw and centre for settlement. This excellent map, by (Insert) makes the point well.

The ford was later replaced around 1014, (exactly 1000 years ago, in the same year of the Battle of Clontarf) by Dublin’s first Bridge. Naturally, this was simply called “the bridge” – since for centuries it was Dublin’s only one. Today’s successor-structure is called Father Mathew Bridge.

When Christianity arrives in Ireland, a few churches and early monastic settlements spring up in the area. The same excellent map above shows some of the early and best–attested church sites, as well as the all-important river Poddle, the Dubh Linn; Usher’s island (which was then still an island) and even the old hurdle-ford crossing point. You’ll also note Áth Cliath, and Duibhlinn appear as slightly separate, distinct places.

But the credit for the foundation of Dublin as a city goes of course to the Vikings. Driven by population pressure in their homeland, and assisted by technological advances in ship building and navigation, they start showing up, marauding and pillaging on Ireland’s coastlines from 791.

They had a permanent settlement, Dublin, from 840, where upon they started to settle down a bit, in both senses of that term. (I mean they stopped pillaging quite so much and started farming, manufacturing, trading and so on instead). They also intermarried with local people and so became a sort of hybrid people Irish-Scandinavian people, whom we call the Hiberno-Norse.

The Vikings or Hiberno-Norse called their town “Dyfllinn” a corruption of the local Gaelic words Dubh Linn, meaning “black pool” – this being the dark muddy lake where the rivers Poodle and Liffey met, which made an ideal shelter for their longboats. I love this image by the way, by the artist Iain Barber, showing the thriving Viking town of Dyfflinn.

We’ve no maps of Dublin from the Viking age. Nor any from the Norman or Anglo-Norman era. Strongbow with his small but superbly equipped and ruthlessly efficient army, took Dublin by conquest from the Hiberno-Norse in the year 1170, when as the Welsh-Norman chronicler Gerald Cambrensis coldly put it, the Vikings “were slaughtered in their citadel”

Four hundred years later, as England in the Tudor era grew richer, more powerful and more centrally controlled, it was Henry VIII who began to assert full and more direct control over Ireland. The Kldare FitzGerald family, and especially the 9th earl Gerard, had ruled Ireland in the crown’s name. But Henry ruthlessly smashed an uprising by Gerard’s son Silken Thomas. The Kidare siege of Dublin in July 1534 failed, while the following year Henry’s Lord deputy Sir William Skeffington besieged the Fitzgerald’s own fortress at Maynooth, got the garrison to surrender on terms, by granting them a pardon, then broke his word by killing the lot. A piece of insincere savagery, known ever since, with bitter irony, as “the Pardon of Maynooth”

Henry then tied up any loose ends by executing both the son, Silken Thomas, and his uncles in London.

Henry VIII also brought in the Reformation, dissolved the monasteries, and renamed Ireland from a lordship to a Kingdom. His daughter Mary, a devout catholic, would reverse the religious changes but her reign would be relatively short. Henry’s other daughter, Mary’s half-sister and successor, Elizabeth I would continue and consolidate the Protestant revolution their father began.

But, surprisingly perhaps, there are no surviving maps until shortly after the death of the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth. You have to wait until eight years after, into the reign of the first Stuart king James I (James IV of Scotland)

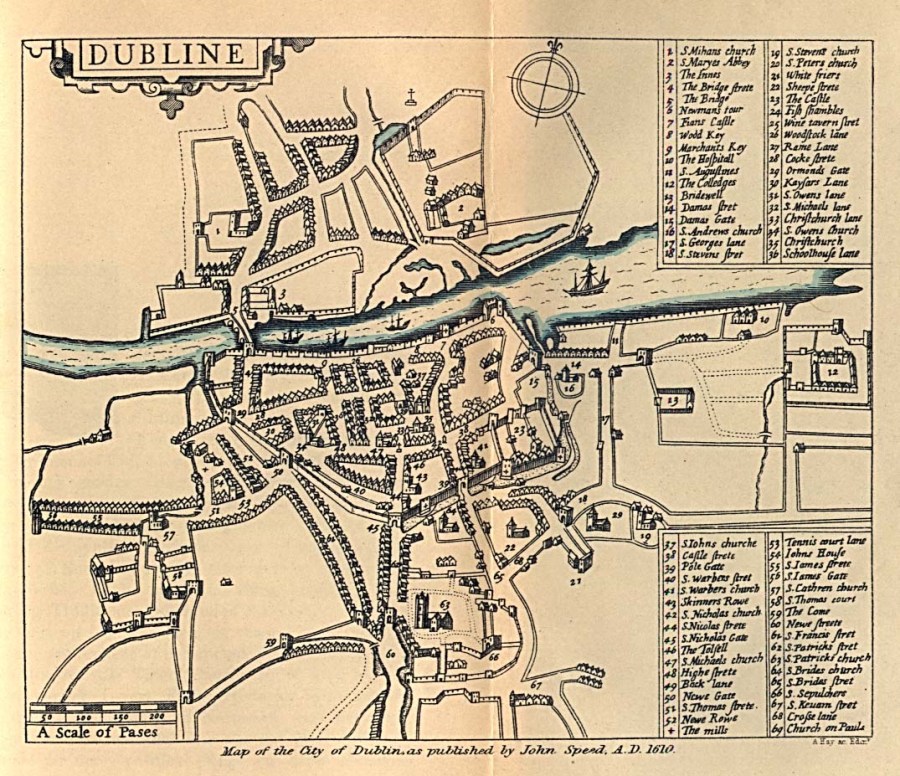

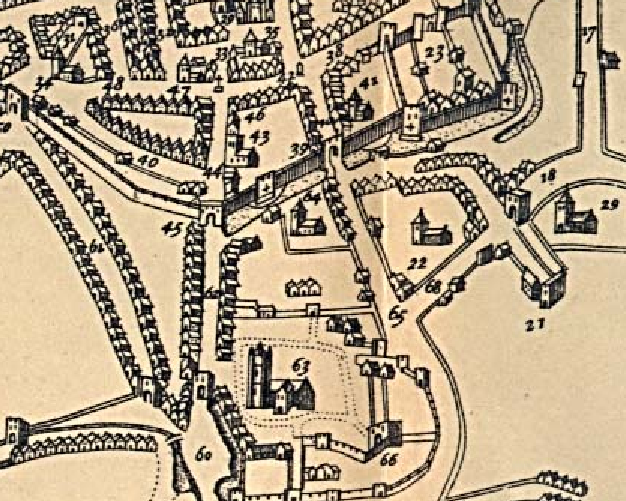

Because in 1610, which by way of context is the same year that Richard Burbage, William Shakespeare and the rest of their actor-producer company (the Lord Chamberlain’s men) move their theatre from the Globe in Southwark to a new site across the Thames in Blackfriars) a cartographer called John Speed shows up and makes the first map of Dublin. Here it is.

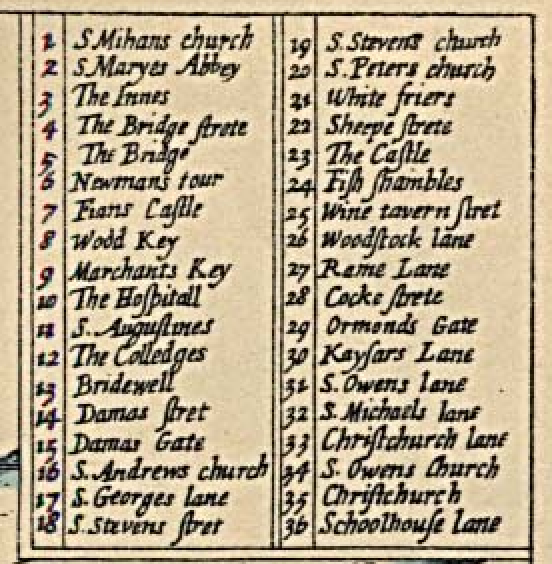

This is naturally a vital source for historians, full of fascinating and vital information. You’ll see how Speed has picked out numerous important ecclesiastical and public buildings. These are numbered in the legend in the two boxes on the right hand side, including important and prestigious churches like #40 Werburgh’s and #34,St Audoen’s. (Both of which good old Speed has spelt a little erratically)

We can also clearly see at once, how the whole medieval Dublin city lay south of the river. You can see that the entire old city was substantially further west than the current city centre. Today we normally think of O’Connell Street- Grafton St axis as “the centre”, but back then neither existed and even if they had, would have been outside and quite far east of the city walls.

No, instead Dublin Castle (numbered #23 on Speed’s map above) mark the south and eastern extremity of the city. Indeed, if we look again, it’s more accurate to say Dublin Castle is the southeastern corner of the city.

Just beyond it is the new university, (marked #12). Elizabeth for religious and political reasons, had encouraged the foundation of the new Dublin University. It was envisaged that this would take the same collegiate path as Oxford and Cambridge. So the first, initial college was called Trinity College. But no further colleges were every founded, the original just got ever-larger and today, Dublin University and Trinity College to all intents and purposes are the same institution. You can see it, to the right of this early map. Trinity College was about 15 years old when this map was made, barely a teenager!

If you still stay on the south side of the river: but go over to the other, left side of the map, find #58, Thomas Court: an important Abbey founded by old Henry II- to atone for the murder of his troublesome archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Beckett.

Also find just above #57 St Catherine’s church, (which Speed has spelt “S Cathren”) As all Dubliners know, this is where poor old Robert Emmet was executed in 1803, having redeemed his shambolic revolt with a brave and justly famous courtroom speech.

In the dead centre of the city, aptly enough, sits #35 Christchurch– founded way back in 1028 in the Norse era- just after the Vikings, rather belatedly, converted to Christianity.

Almost immediately left of it, see #47, Saint Michaels, which no longer exists but in 1610 was still clearly an important church.

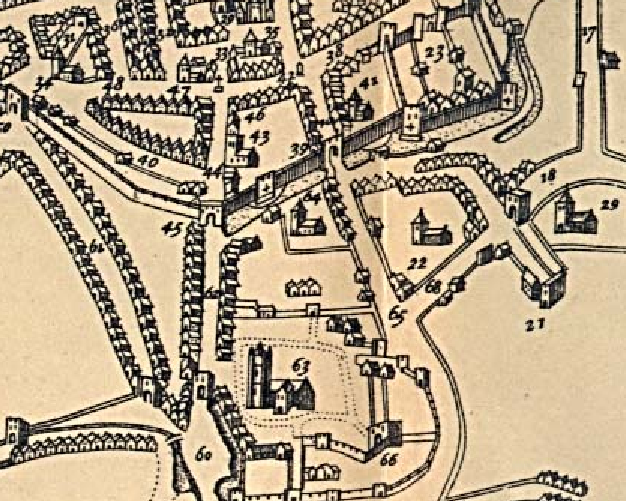

Now draw a line, hard south, from between these two ecclesiastical buildings, and you’ll pass through the medieval city walls under #45 St Nicholas’ Gate (one of the 6 great gates of the ancient city) which is overlooked in turn by #44, St Nicholas’ fortress, (which was really more of a defensive tower).

If you follow that same road south, you’ll come to #63: St Patrick’s; founded as a great colligate church around 1189 by Archbishop John Comyn, then raised to the status of a Cathedral by his successor Henri de Londres a few years later, meaning Dublin (uniquely,) now had two cathedrals. You’ll see St patricks appears bigger on Speeds map and that is probably not just a matter of perspective. Ever sincesits foundation in the 12th century it has been larger and more important than Christchurch.

Or, instead of proceeding south on this southwards road, go back to #45, St Nicholas’ gate, and look East instead. Do you see the way there is a river, the river Poddle, that flows all the way around the south wall of Dublin Castle, forming a moat? Today the Poddle/moat has been culvert’ed over. It is is now a road called Ships Street.

Follow the river/moat, as it turns the corner of the castle and goes a small way north. You’ll see the river widens slightly, as it turns the corner. This is a dam. (the Anglo-Normans were of course superb engineers, especially when it came to military architecture and defense) The superb artists impression below makes the point well, and there’s a second enlarged detail below again.

This dam, by the way, is the origin of the name “Dame Street” a name which has nothing to do with an old dame, or “notre dame” or anything like that, but is simply a corruption of the word dam. Near the dam was another of the city’s great gates, Dam or Dame Gate, marked #15 on Speed map. (in the image below it stands guard over the bridge)

There are hundreds of other bits of vital historical information in Speed’s map. Look on the north bank again and you’ll see important examples. There are not many major settlements north of the river. Few enough we can list them.

They are, #1-the church of St Michan’s, which for a very long time was the only church on north of the river. The cluster of houses above it by the way is the “suburb” of Oxsmanstown, established when the victorious Normans had booted the surviving Hiberno-Norse out of their own defeated city in 1170-71. In fact the name Ostmanstown, simply means the “town of the Ost-men” which is what people at the time called Vikings and Norse.

Back on the river, #3 is “the Innes” or Inns, meaning the Kings Inns, meaning the home of barristers and the legal profession. This is where the law library and benchers were. The actual courts did not move until slightly later. James Gandon’s famed Four Courts building was not until much later of course, the 1790s, at which point the Inns moved North again to their new, magnificent home, (also by Gandon) between Henrietta St and Constitution Hill, which at that point sat facing open countryside.

The old Inns by the river sat in turn on the site of a religious house, but this is gone and demolished. Why?

Also on the north side of the river, #2, is another religious foundation, St Mary’s, still intact. But if you know your history, you’ll know it must have been an empty shell by 1610.

The monasteries of England, Ireland and Wales had been dissolved back in the 1530s by Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII. Yet the buildings and high curtain walls of formerly the richest, most important Dublin religious house, the Abbey of Saint Mary’s, are all clearly still standing and intact, fully 80 years after all the monks were thrown out, now in 1610 during the reign of her successor, James I, when Speed drew his map.

It would be another 65-70 years before these walls and the Abbey were torn down. That was all done by the highly entrepreneurial builder–developer, Sir Humphrey Jarvis, who cannibalized the old abbey for building materials. Large sections of Jarvis’ old Capel Street, and the old Essex Bridge, (which predates Parliament street, the modern version is called Grattan Bridge) were both made of stone from the Abbey.

This once the all-powerful St Mary’s, biggest landowner in Ireland and wielder of immense power, both religious, temporal, political and economic. For example the Abbey controlled the entire food supply of Dublin; they’d also had their own courts and powers of trial and execution. Now it lies empty. In time it will be pulled down completely by Jarvis.

For hundreds of years it was thought nothing of the Abbey survived, but in fact the Chapter House somehow did, albeit hidden and buried underground. We sometimes visit this incredible old survivor on our Dublin Decoded tours (see below)

In the next installment of this post, we’ll show you how Jarvis’s developments, and further expansion just 20 years later, by old Luke Gardiner, changed the shape of old Dublin, broke the city from within the medieval walls and even reoriented the whole axis of the city.

If you enjoy walking your history as much as you enjoy reading it, we lead a 3-4 “Dublin Decoded” history walking tours around the city each month, focusing on different themes and ideas, from medieval through Georgina to Victorian and beyond. In fact Dublin Decoded run both public and private guided walking tours of of Dublin’s built heritage and history: including explorations of the Georgian era, Modern and Victorian, social, cultural and political history and even tours of Medieval Dublin’s walls. To see details of our famous Dublin Decoded public, guided walking tours, to which all are welcome (tickets average €19 pp) please go to the Public Walks page of our tours website. Be advised, we run just 2-4 public tours each month, they are only scheduled 8- 25 days prior to each tour, and they nearly always sell out. This useful monthly newsletter will let you know if or when new public tours go ahead. Alternatively, to see the possibilities for booking a private tour, on a date of your own choosing, for your own group, please go to the home page of our tours website, see the available featured tours, then follow the steps to book your tour. Private tours from €200, for your entire group. All information on our tours is on the respective tour pages.

Either way, whether you join one of our public walks, to which all are welcome, we look forward to welcoming you on tour!

Reblogged this on Call of the Siren and commented:

Arran Henderson gives us the next best thing to a time machine in this post, my friends. He also supplies surprising etymological details too: How could one of my favorite cities ever have been named after muddy water? I had no idea. My favorite city, and my favorite bluesman, too! Enjoy…

LikeLike

Many thanks Siren! much appreciated. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh for a second life, to be able to read this kind of wonderful stuff all day 🙂 Tremendous post, Arran. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your kind words Jane. Chuffed to bits you enjoyed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Kat Webber and commented:

Amazing! I would love to go back 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks a million for the re-blog Kat, it’s much appreciated. Also just delighted you enjoyed the piece yourself. Come back to Ireland anytime, and drop us a line here when you do. and/or come on one of those walking tours I mention above, it would be a pleasure to have you along. kind regards- Arran.

LikeLike

Hi Arran, really enjoyed this post, thanks. There’s something so satisfying about following the evolution of a city through maps, even (or especially?) if those maps are few and far between.

LikeLike

Hi Aileen, thanks for the kind words, really glad you enjoyed it all. Totally agree with you about the pleasure of old maps. Wait until you see the one in the next post, it’s extraordinary, something of a miracle. warm regards- A.

LikeLike

Thank you for this interesting history. Do you also know of the plan drawn up to make Capel Street the focal point and main street of Dublin in the newly independent Ireland of the 1920s?

LikeLike

Hi Andrew, thanks for your comments and my pleasure. As for the question, I’m afriad I don’t know enough – about the Capel St plan you mentioned- not off the top of my head, to give you a worthwhile answer. But if you find out more, or a really good link, please drop me another line here, as naturally I’d be interested. Thanks again for the comment.- Arran.

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff Arran. I wonder if those huge islands in Ptolemy’s maps are meant to be Ireland’s Eye & Lambay 🙂

LikeLike

HI Roy, nice to hear from you, and many thanks. Yes i think they must be Ireland’s Eye and Lambay, that’s certainly what I assumed too, it would make sense. Nice to hear from you- Arran.

LikeLike

love these tales there like beer to a drunkard, can you tell where i can get old street map of dublin that marries up with the 1851 to 1901 cencus, street have change since then Tyrone street , Glouester street ,sackville street mabbot street , and many more streets, where my family have lived .all of them changed

LikeLike

Hi Brendan. I’m charging out the door now, but yes, there are plenty of maps from that period, even a Google image search will turn up a few really good ones. Good luck with your family history research, sounds very interesting. -Arran.

LikeLike

How good is this?! You are such a gem in the dublin life. Impressive.

LikeLike

Thanks Owl! Very chuffed and delighted you enjoyed. 🙂

LikeLike

Oh, of course!

LikeLiked by 1 person

i wound like to know where the name Mcsweeny came from my greatgranddads name was john McSweeny who came dublin.

LikeLike

Hello Charlie, I do know some Mcsweeneys here, from County Sligo (in the west of Ireland) But I’m not the best man to ask about this subject in general to be honest. There are however specialist genealogy firms and even free genealogy websites. You could also try the census reports, a very very useful resource. It’s All findable via Google and all up on the web! Good luck with your research. best regards- Arran.

LikeLike