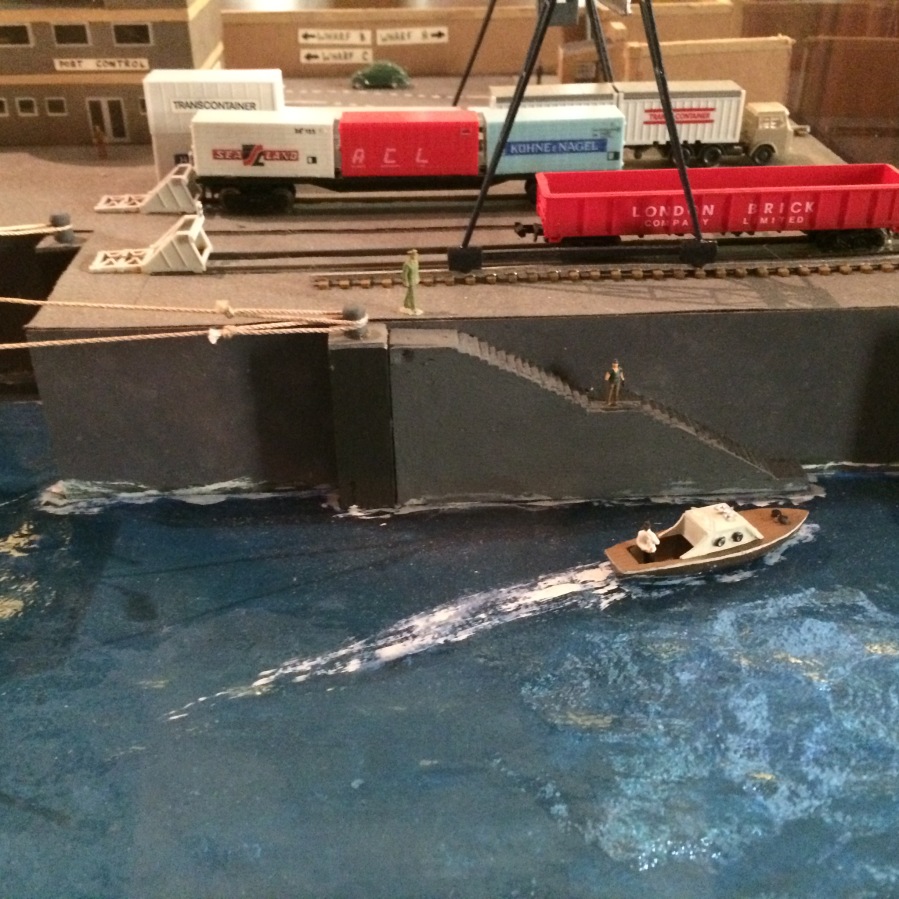

This little display case with its wonderful ship model, was spotted at Dun Laoghaire’s terrific Maritime Museum over the weekend, (the museum is on Haigh Terrace, near Dun Laoghaire’s new public library (pay a visit to both when you can).

It put me in mind of a subject close to my heart. Because this isn’t just a model of a ship, it’s a whole tableau. With its tiny but virtuoso representations of rich blue sea; it’s dockside; cranes; warehouses, rucks, trains and vans, and smaller craft bobbing or rushing about, it’s a small, manageable slice of our big complex world, scaled down for a better understanding, re-made as a model. In other words: a diorama. And personally, I love ’em. Look at the little speed boat in the second picture below, with its white wake. Who couldn’t enjoy that?

Life sized or small miniature scale- from a trout in a fisherman’s case with a simple blue painted background, to a tiny ship in a bottle- the act of simply capturing or seeing a slice of world in illusionist three-dimensional form seems to speak to some deep human impulse. My first memory, aged 3 at the space museum in Moscow, was a mock-up of Cosmonauts floating in space beside their spacecraft, in front of a deep rich inky blue, a simulacrum of outer space. (I’ve been unable to find a good picture of this. As you can imagine, I’d love to get my hands on one).

Later, like boys the world over, I made my own models, landscapes of hills and trees, to populate with troops of tin soldiers, complete with flags, horses and cannon. (The 18th century seemed to be the main era, don’t ask me why) Soldiers were cast from a mix of tin and lead, (then painted with lead-based paints). Those bread trays bakers use delivery shops were pressed into service as a base for the the landscapes. And although most the hilly terrains were shaped from mashed soggy newspapers allowed to dry then covered in plaster of Paris, others were carved with a hot knife from blocks of expanded polystyrene!

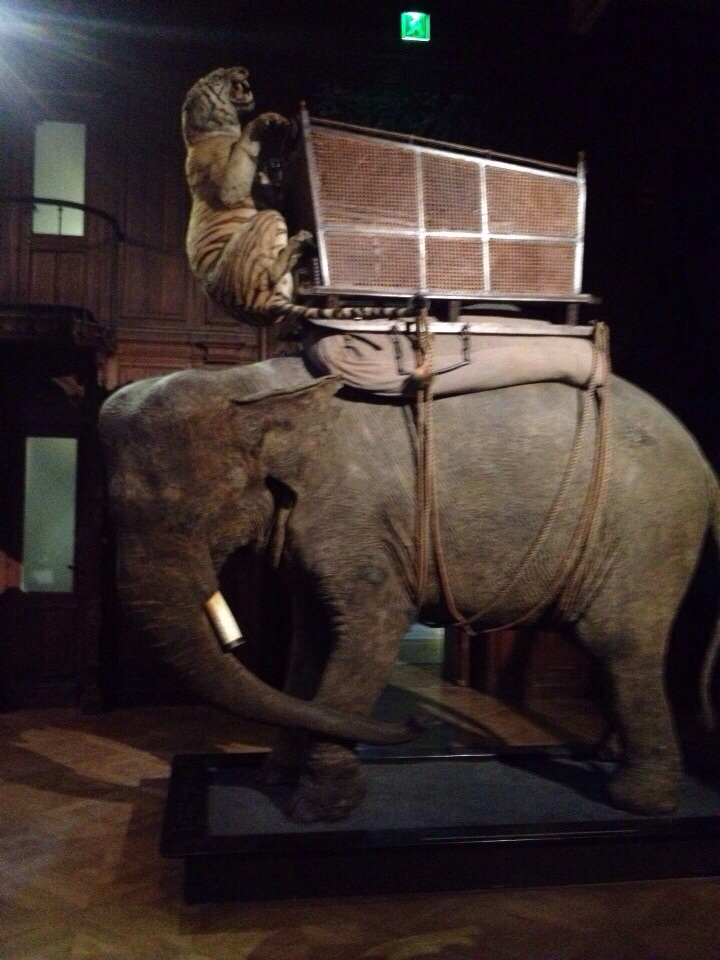

To get back to the professionals, you could say there are two types of diorama: the miniature, and the life-sized. For obvious reasons huge scenes like this above (ships, factories, battle scenes and so on) are usually in miniature form. Conversely Natural History tableau of animals in nature are mostly 1:1 scale, since those type of museums use real-life stuffed specimens. In a true tableau however, the inclusion of a realistic landscape, including deep background, still presents a challenge to tableau artists. The lovely Victorian display cases in Dublin’s natural History Museum by the Dublin firm of Hicks, although not as spectacular as New York’s vast scenes , still represent a beautiful case in point.

In contrast, in miniature tableau one tends to look down on the scene, spread out like a 3-dimnsional map, so the creation of depth is less of an issue.

This post, from November 2013 was sparked by a visit to Munich’s Deutsch Museum and by this terrific geological diorama there. It falls into the miniature category. The illusionist impression of space, with forced and atmospheric perspective, is masterful. Diorama makers frequently use curved walls in the background, to enhance this effect and to “focus” the background on infinity.

You have to love the intrepid little geologist, looking out into and contemplating the sublime. Can you see him?

You have to love the intrepid little geologist, looking out into and contemplating the sublime. Can you see him?

Does one detect the influence of a famous picture? Perhaps by this famous image below by Casper David Fredrich. This is a sort of emblem of German (and international) Romanticism, so who knows?

Does one detect the influence of a famous picture? Perhaps by this famous image below by Casper David Fredrich. This is a sort of emblem of German (and international) Romanticism, so who knows?

The Germans and British both have their fair share of dioramas. But since the early 19th century the French oddly enough, never seem to go in for it. This is odd since early 19th century Frenchman Daguerre gets credited with the invention of the tableau. Perhaps the distinction is that he used them in a theatrical and artistic context, creating “spectacles” with a clever use of scenery and changing light effects for his paying visitors. (A sort of sideshow to the theatre or art gallery, yet also a precursor to cinema)

A year after they debuted in Paris, Daguerre’s tableau were bought up and shipped to London, where -once installed in a building designed by A.C. Pugin in Regent’s Park- they became a sensation and very fashionable attraction.

In time dioramas would be adopted for educational and museum use. But in contrast since that point the curators of France’s great museums appeared to have rather sniffed at the idea. Tableau of course are not really suitable for Art museums, where paintings and sculptures speak for themselves. (Nobody it appears has yet thought of placing the Venus de Milo in front of a painted backdrop of ancient Milos!) They are however commonly used in museums of science (like the Deutsches) or more commonly at Natural History museums. But the French don’t seem to have done this either. Compared to the spectacular museums like the Lourve, or D’Orsay, Paris’ Natural History Museum is oddly underwhelming. It was considered almost dowdy for years. Recently it’s had a modern refit, But although the lighting far more dramatic and effective, there are still no true tableau in sight.

In contrast Mitel-Europe and the Anglophone world both wholeheartedly embraced the tableau, primarily as a vehicle for education. (Only more recently has they also been recognized as an art form in their own right)

There was apparently a superb series in the Royal Services Institute in London depicting a series of battles, funded by a wealthy German Jewish philanthropist Otto Gottstein. It told history through images of war, depicting battles from Caesar’s Invasion of Britain and Crusader Richard I at Jaffa (admittedly a brutal affair) to The Charge of the Light Brgade and the D-day landings.

Sadly this collection was broken up and dispersed around other museums (including in Canada and around the UK). The museum was closed i 1968 but it’s a shame this wonderful series could not have been kept together and intact. One suspects in the 1960s it was considered embarrassingly jingoistic, nostalgic, even offensively imperial in its sensibility. Too much political correctness perhaps?

So to some extent the tableau-diorama fell from fashion in the post-war period. But I think today we all recognize how wonderful they are, how evocative and how they speak to deep within us. Recently they have been recognized as an art form in their own right. This may be speculative, but could this return to favour be something to do this my own generation, raised on the films of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg? All those Star Wars models; all those dinosaur kits? It may be a stretch perhaps, but I think it was bound to have an effect on a generation.

Outside Dublin’s Natural History Museum, with it’s wonderful display cases, most of Ireland’s other tableau are made by very skilled local artists, generally in local institutions like Dun Laoghaire’s great Maritime museum. As a rule they depict historical or archaeological sites. Here’s one of the Cistercian monastery of Melifont, (County Louth)

and another below of the Celtic monastery Glendalough, in County Wicklow from the interpretive centre there.

Oh here’s another I found. (Oh dear, I seem to my embarrassingly large collection of such images, !) This one is of the old quays at Waterford, from the wonderful medieval museum in that historic city. (Highly recommended)

So Ireland holds her head high, in this mighty (or miniature) battlefield!

However, as you might expect a quick glance around Google or Wikipedia reveals that from the turn of the 20th century, United States dominated the world of tableau. If one wants to see the true block-busters of the genre, one must head Stateside.

In fact the Americans more or less invented the educational museum diorama. They are certainly the masters of it. Philadelphia’s Natural History Museum is apparently the oldest such institution. But the first diorama-proper was created for the Milwaukee Public museum in Wisconsin, designed by Carl Akeley. He is now considered the “father of modern taxidermy”. That accolade hardly does him credit, he seemed to be a wonderful innovator in so many ways.

His masterpieces are the amazing, spell binding tableau in New York’s American Museum of Natural Sciences. These are perhaps now the greatest tableau in the world.

I was lucky enough to visit in July this year. As you might expect, my inner anorak took hold. I took an awful lot of photographs! But I make no apologies, these tableau really are amazing, justly famous, and considered the masterpieces of the genre. Here is a small taster, below, but as soon as i can I hope to show you a bigger cross sample in another post, coming soon.

By the way, with the exception of the Caspar David Frederich picture (from wiki-commons) all photos here are my own throughout. So please play nice, if you use or share just acknowledge source and provide link back to my blog. Thank you.

Until then, thanks very much as always for reading, and goodbye for now. -Arran.

Thanks for posting this, Arran—the kind of stuff I can look at for hours 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Jane Dougherty Writes and commented:

I love the multiple dimensions of these exhibits. Wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

and many thank for re-blog Jane, very kind. Ax

LikeLiked by 1 person

Models and dolls certainly appeal to deep-seated instincts in us. Is it an emotional thing — something to love and perhaps have unconditional love returned — or merely a power thing — master-of-all-I-survey like Crusoe n his island? Or is it what really sets us apart from other primates, that instinct to be a Creator, a demiurge giving birth to a world of our own making? Or all of these, maybe?

Anyway, great post and lovely photos, Arran, must go back and look at the rest of the posts in your series that I’ve somehow missed.

LikeLike

I think you are right, it is all three of the above. But your perceptive comments have given me pause for further thought on the subject (Now I’m not shackled by having to write about it i can think about it again, as it’were!) On reflection i think your 3rd reason may be the most powerful. In other words that “master of all we survey” sense, of ownership you mention.

Of course ownership can take many forms. By collecting something (like wild and exotic animals say) we prove we have “been there/ seen that”, even “conquered them” And of course most of these species were shot/fished/ collected in a more, ahem “robust” Victorian/Edwardian age, when if a man (say Teddy Roosevelt, main collector behind the NY collection) saw a wild animal, he generally wanted to shoot it. So there’s that sort of ownership i suppose, de facto conquest.

And then extending the idea you suggest, the idea of model-making in particular, (miniature or otherwise, even modern computer models) is also powerful form of both owning, and understanding.

One can’t built a model of something without a thorough understanding of its size, shape, structure and so on. So by making a model, we essentially prove we understand it. (even if the process of model-making was itself the partial or even the crucial key to that understanding)

Please don’t ask me the source, but I think I recall hearing once there’s an actual principal in theoretical physics, which states we can not build a model (of any sort) of an object/ shape/ system, which is more complex than ourselves, (only of one less complex). This may explains why we can (more or less) understand the ant, but not visa versa. Or equally why we will almost certain continue to struggle for any full or complete picture of the universe, its shape or origins. When we do model something it demonstrates our mastery of understanding. And of course the model itself then becomes a powerful vehicle for explaining that knowledge to others, vis a vis graphics in a history documentary, or a scale model of a castle or monastery in a local museum, or one of a complex battlefield, or a dinosaur.

Thank you very much for your thoughts, great food for thought.

To be honest I’m both relieved and delighted to discover somebody finds this topic as fascinating as i do!

-Arran.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very nice! And we have a diorama in Atlanta, of course, it’s the civil war. I should go visit it again, it’s been ages.

LikeLike

I couldn’t resist the temptation to Google your Civil War diorama there in Atlantic and found a picture of it. Looks to be a really spectacular one! Delighted you enjoyed the piece. Thanks for comment. 🙂

LikeLike

[…] Source: Tableau & Diorama. (iii) […]

LikeLike

I seem to remember a short story, perhaps by Jorge Luis Borges, about someone building a model of something or other, but it was lifesize, the idea being to ask when does a model become the thing it’s a copy of? Must look that up to check how accurate or faulty my memory is.

Glad I spurred further thinking on models, Arran, and look forward to a possible future post about it!

LikeLike

That sounds like exactly the kind of thing Borges would write. There’s nobody better for picking up an idea, like a sphere or a maze, and just turning it around and playing with it, and seeing where, (in the light of his extraordinary erudition) he could take it.

I must try and find that story too. Sounds intriguing. Thank you!

LikeLike

maybe a bit off-topic… but quite interesting: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5sTTwkwk1XV2BNDWC4rly5w/blade-runners-model-shop-see-inside-a-sci-fi-classic >> http://imgur.com/a/mv8qf

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not off topic at all. Models are models. And I have a big soft spot for Star Wars and Sci-Fi type stuff anyway. 🙂

LikeLike