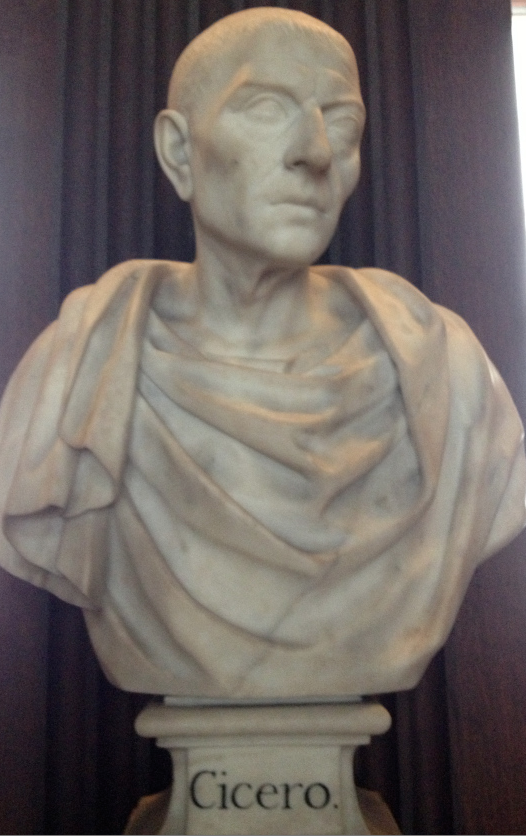

Look at this bust of the great Roman orator, statesman, and lawyer, Marcus Tullius Cicero.

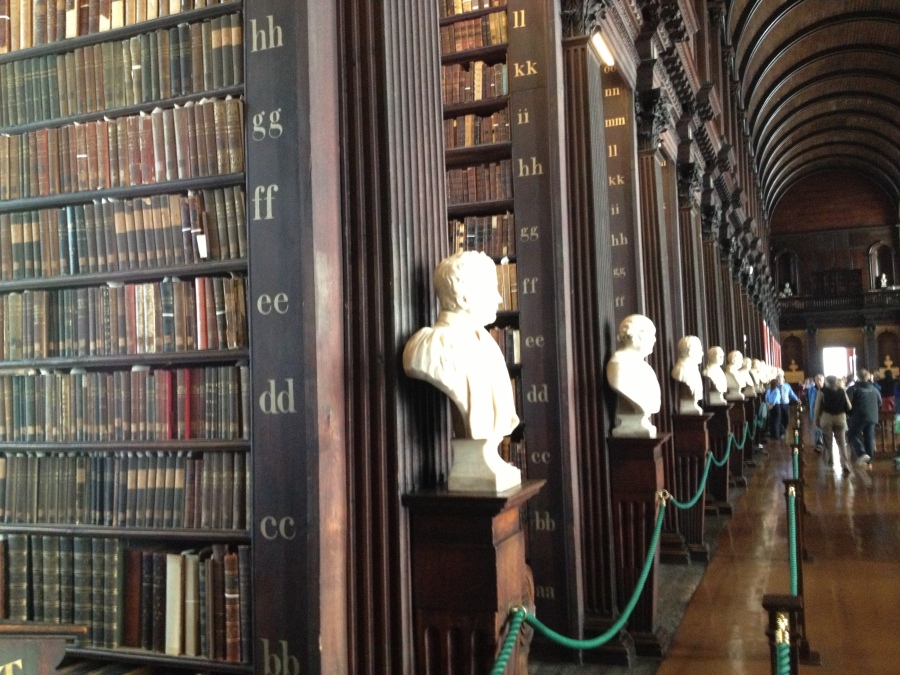

It’s by the Flemish sculptor Peter Scheemakers (1691-1781) who in the 18th century was commissioned by Trinity College to carve the first 14 figures for their collection of marble sculpture busts featuring famous thinkers for the old library of Trinity College.

The main old library interior, commonly called the Long Room, is arguably one of the most beautiful rooms in Europe.

The old sculpture busts that line its galleries between the lovely old bookshelves are very much part of the beauty and overall atmosphere of this wonderful place.

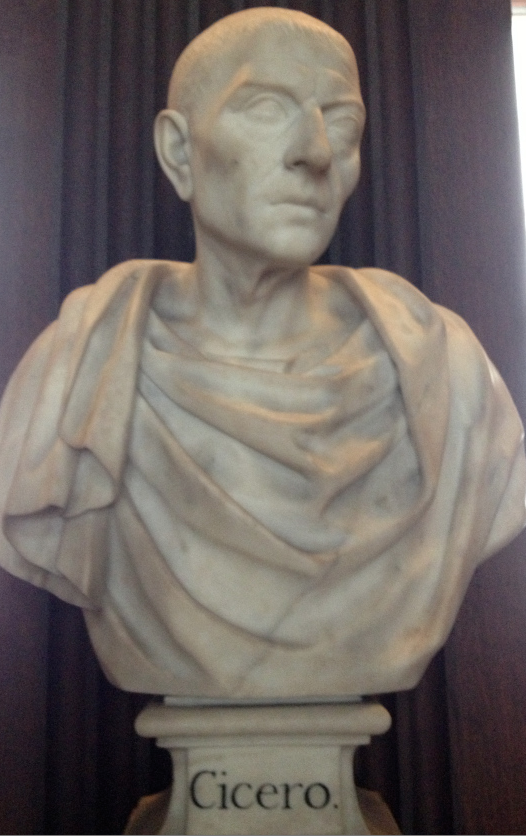

And who was the sculptor? Well, much of Scheemakers’ career (and very long life) were spent in London. Although you may not know his name, you almost certainly know at least one of his works. It was Scheemakers who sculpted the famous bust of William Shakespeare that sits in Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, a work endlessly reproduced and indeed one that forms a large part of our ideas today of how Shakespeare looked. Scheemakers made a Shakespeare bust for the Trinity Long Room collection too by request, as part of that core group of 14. But it is another one Scheemakers’ busts in the Long Room I’d like to discuss here. His bust of Cicero. Essentially, I am going to suggest that this figure or face (below) is not Cicero at all. In order to do that, but also to spell out why it still matters, I’m going to discuss Cicero and his career, as well as the intertwining lives some of his equally famous contemporaries. Then I’m going to look at some other, rather different, images of Cicero to provide points of comparison. Finally I’m going to suggest another, alternative identification for this statue currently labeled Cicero, namely one of those aforementioned contemporaries and provide images of that man to provide points of visual comparison, so you can make up your own mind. The fact both men hail from the same era will, I hope, justify the long detour through Roman history. Which I’m secretly hoping you’ll actually enjoy. Personally I love Roman history and can rarely get enough of it.

It may be useful to remind ourselves who Cicero was. With respect to our Flemish artist, his bust looks nothing like Cicero. Even before I knew what he looked like, this was never how I imagined him. He was a robust, worldly character, not an aristocrat or patrician but a self-made “new man” well built and well-matched for the rough and tumble of the Roman law courts and politics, in those extraordinary last decades of the Roman Republic. He was a man for wheeling and dealing. Yet as a senator, then consul, he also became something of a champion for liberty too, as he fought to defend and preserve the constitutional institutions of the Roman Republic. It was Cicero who faced down, exposed and then punished the Catiline conspiracy.

Cicero Accuses Catiline (also known as Cicero Denounces Catiline) By Cesare Maccari 1888

Cicero and Catiline, by the history artist Schmidt, image taken, believe it or not, from an auction on eBay

Cicero is partially defined by that conspiracy of the desperate scheming Catiline and by his own prompt action to defeat it. Even more than that, slightly later in his career, he’s seen as somebody who battled impossible historical forces, forces which were leading inexorably to the eventual extinction of the venerable, highly successful Roman Republic.

This meant Cicero had to deal with some of the most powerful men who ever lived, as they competed for glory and jockeyed for ever greater power. The context here is crucial. Rome’s ever expanding empire, with its vast territories under direct control (and even larger areas and scores of client states just outside areas of direct rule) offered unimaginable power and wealth to those who commanded the top jobs and most lucrative foreign posts. The Republic was full of clever, confident, ambitious men, hungry for such wealth, glory and prestige – Luculus, Mettelus, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, Curio, Cato the Younger, and scores of others. But even more than these were the three dominant figures who sit astride the history of the late Roman Republic and whose names live forever in history. They were firstly Pompey the Great. In his youth he’d been a protege of the former dictator Sulla. Pompey became a highly successful young general who emulated Alexander the Great, winning vast territory and riches in the east. Secondly, the legendary Julius Caesar, and third Marcus Licinius Crassus, former consul, destroyer of the Spartacus Slave revolt, and, famously, the richest man in Rome. Don’t think of these men as simply like some British or French aristocrats or grandees, with large landed estates or titles, or seats in the House of Lords. They were far, far more than that. In reality they were more like Kings, who at times controlled entire countries. Indeed they were more like “over-kings” since they counted mighty eastern Kings or Egyptian Pharaohs among their clients. But within the long established Roman system. And Rome was still a Republic, albeit a Republic with an Empire. This huge power wielded by these three men is what made other Roman patricians nervous. Romans hated kings. They were proud of their Republic and its constitutional democratic system, which drove men to excel and compete but which also contained a careful system of checks and balances designed specifically to avoid dominance by any one individual or family. Men like mighty Pompey, the unbelievably rich Crassus, or now, the youngest member Caesar, threatened all that.

above: Pompey the Great, victor in the war against Mithridates and conqueror of large parts of western Asia and the middle east including around the Black Sea and modern day Armenia. He also built the vast Theatre of Pompey complex, (below)

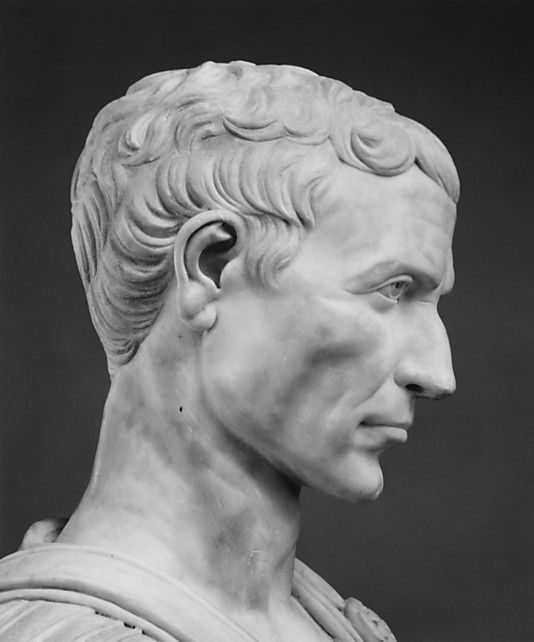

above: Julius Caesar, conqueror of Gaul and large adjoining parts of western Europe. Perhaps the greatest military commander in history.

Initially, the fierce competitive spirit typical of Republican Rome helped keep the three men apart. This was helped by the deep and mutual loathing between Pompey and Crassus. But when – prompted most likely by Caesar – these two put aside their differences and formed an alliance along with Caesar, an alliance called the First Triumvirate, the three together became unbeatable. They couldn’t do absolutely anything they liked, they were occasionally frustrated. But it was close; they could do an awful lot. They could also (and crucially) prevent anybody else taking any actions, or passing any laws that might go against their wishes or against their interests. Even still, the three men courted Cicero, craving his imprimatur or approval. The Republic and its ideals still mattered. And after defeating the Cataline conspiracy Cicero was often called “the father of the Republic” meaning the defender of its institutions. The Triumvirate were anxious to have his approval. Or, at the very least, to escape his censure, if possible. They more or less invited him to join them. He refused. Cicero was more anxious to defend the Republic and its constitution against this threat of overweening power, no matter the dangers, no matter either the incredible, extraordinary rewards on offer for his compliance. His dignity demanded it. So too did his well-developed sense of his special place in history. History has more or less vindicated that judgement.

After the death of Crassus in 53BC while on military service in the east, the Triumvirate was finished. The balance of power became unstable again. The Republic soon faced another even greater threat. One of the problems was that Caesar had proved to be an incredibly successful commander in Gaul.

Vercingetortix throws down his arms at the feet of Caesar, by Lionel Royer 1899

As he won victory after victory, over nine years there, as well as excursions into modern day Belgium, Holland, Britain, and Germany, he inevitably assembled a huge army of hardened veterans.

These legions, loyal only to him, made Caesar dangerously and independently powerful. The veterans, not unreasonably, also expected land from the Roman Republic, in return for their long service to it. But many of Caesar’s enemies in the senate, men like Domitius Ahenobarbus and Cato the Younger, were unwilling to grant such land or pass the laws or the funds necessary to purchase it. This set them on a deadly collision course with Caesar. When these enemies of Caesar’s, full of both jealousy and fear, threatened him with prosecution and demanded he lay down his Imperium (his command) he was faced with a stark choice. He instead crossed the Rubicon on 10 January 49BC to invade Italy itself. This started the civil war. As they had not time to muster an army, his invasion drove most of the senate, including Cato, Cicero and Pompey, out of Rome and Italy. They assembled across the Adriatic, reassembling in the Balkans, putting themselves under the military command of Pompey to face the enemy.

It was a shrewd move. Caesar followed them across the Adriatic. But without sufficient transport ships he had only half his army (some of his other troops followed piecemeal). He was also low on supplies. Facing chronic food and supply shortages, and with a significant numerical disadvantage, Caesar still somehow fought a stunning campaign that ended in shocking and decisive victory at Pharsalus. The defeated Pompeians either died in battle or committed suicide, others fled elsewhere if they could escape. Significant numbers came over to Caesar’s side, including one Junius Brutus. Pompey himself, the great commander, fled to Egypt. Cato also went to other Roman colonies in North Africa. But he went further west, to what is now Tunisia, historically Carthage. Here the remaining anti-Caesar factions regathered and regrouped, rebuilding their army, and finding new allies. These included one King Juba, head of a mighty army featuring (like some later-day Hannibal) a cavalry of war elephants.

It is ironic that Cato ended up in Carthage. His ancestor, a great grandfather, was a famous and famously stern Censor, Cato the Elder. Cato the elder lived at a time when old Carthage, the mighty trading and military power of the western Mediterranean, rivaled Rome itself and threatened her chances of expansion and supremacy. Cato the Elder used to finish every single speech with words along the lines of Carthago delenda est (Carthage must be destroyed) Back in 146BC Rome did indeed destroy old Carthage and sell its inhabitants into slavery. It was planted with loyal Roman subjects and became a dependent colony. It was here, paradoxically, that Cato the Younger would make his last stand.

Cicero by contrast did not go to North Africa or to Spain, where another group of Pompeians were gathering yet another army against Caesar. Cicero now sensed the war was over after Pharsalus. In despair, he returned to Italy, somewhat fearfully, unsure if Caesar would tolerate him or have him executed. As it turned out Caesar, now declared dictator back in Rome by his supporters – but still anxious to restore some sense of normality and tradition to Rome – was more than happy not just to tolerate but to honour the great orator. Caesar was in any case famous for his clemency, most unlike some of the notorious 2oth century dictators, who were merely paranoid, cruel and vicious. On the other hand Caesar’s right hand man, his violent tempered deputy, Mark Anthony, was less inclined to be forgiving (a sign of things to come). But for the time being at least Cicero survived.

It turned out Cicero’s instincts about the war being lost were correct. After his victory at Pharsalus, Caesar pursued Pompey across to Egypt. But before he could even reach it the feuding Ptolemaic Egyptian palace factions had his great rival murdered. Ironically they did this in order to please Caesar. In reality he was disgusted by their treachery, he is said to have wept. The war was not yet over, but after 10 years of almost continuous war command, in Gaul and elsewhere, Caesar now chose this moment, in the the middle of a civil war, to have a break. He first sided with the young queen Cleopatra in support of her claim to the throne and again defied the odds by routing the opposing Egyptian army.

Cleopatra and Caesar, Jean-Leon Gerome. 1866. A young queen effects a charming introduction, by means of a carpet. (It was actually inside a carpet bag my sources say)

Then, once again victorious, he granted himself some leisure to go on a lengthy Nile cruise with the young queen. He finally turned his attention to the civil war again, and in his final two separate campaigns Caesar defeated Scipio and Juba’s army at Thapsus in modern day Tunisia (former Carthage). Then he killed off Pompey’s two sons in another campaign in Spain, in the battle of Munda. He was now utterly triumphant, unassailable, easily the most powerful man in the world, perhaps in history. With Caesar unassailable, Rome was temporarily at peace, at last.

Cato died, by his own hand, in Carthage, after the battle of Thapsus, stabbing himself then pulling his entrails out to be sure of death and to avoid any possibility he would have to “submit to the mercy of Caesar”. Caesar was famous for both his generosity and his clemency, fond of pardoning his enemies, especially distinguished fellow Romans. Cato had no intention of giving him such satisfaction.

Cicero, in Italy, was finally allowed back in Rome itself, where lived on under the shadow of benign, rather civilised dictatorship. But dictatorship it was nevertheless. So, while it might seem ungrateful that Cicero rejoiced when the dictator Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March 44BC, we should not be surprised. This was a man who defined his whole life trying to defend the Roman constitution against despotism and tyranny. We cannot be surprised.

The Death of Caesar, by Jean-Leon Gerome.

The conspirators were headed by Cais Longitudus and Junius Brutus, but included (more rank ingratitude) young Decimus Brutus, a son of Caesar’s great mistress and longtime friend Servilia, and thus a sort of favoured and trusted stepson to him. Caesar was dead and his long utterly dominant shadow removed at last. But what was to happen next? Could the Republic be restored? Cicero’s alarm and complaint was not that the assassins had killed Caesar but rather that they had failed to also kill his violent henchman Mark Anthony.

Still worse, instead of taking some sort of control, by going to the senate or or at least to the Rostra in the forum to explain their actions to the Roman public, the conspirators instead huddled uselessly at the top of the Capitoline Hill. They managed to get away from Rome but they had lost the city itself and the initiative and with it the chance to explain or defend their actions. Again Cicero was right to despair. The heirs to Caesar, Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus, and Lepidus now formed a second Triumvirate. They pursued Caesar’s killers relentlessly until they were all destroyed and dead. Rome would never be a Republic again. After another civil war, this time between Octavian and Mark Anthony, Octavian emerged triumphant. He became the first in a long line of Roman Emperors that would last 500 years, or over a thousand if one reckons on the eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium). The Republic was dead.

It is fitting that Cicero died with it. When Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus, and Lepidus formed the second Triumvirate, as sign of good faith they each agreed to nominate somebody they liked, and to nominate someone they wished to destroy. Mark Anthony had always hated Cicero, especially since the Philippics,the great orator’s series of speeches attacking him. He demanded the death of Cicero. Octavian was fond of the old man, as his adoptive uncle had been. But he willingly gave him up.

Professional assassins came for Cicero, army veterans, and he offered them his neck. They did not hesitate. His head and hands were cut off and brought to Rome. They were nailed up in the Forum. In revenge for Cicero’s harsh words, his silver dizzying oratory, Mark Anthony’s wife pulled out the tongue of the dead man, so she could stick a blades or needles through it.

I suppose I’m marked by reading too much Roman history (by the likes of Mary Beard, Adrian Goldsworthy and Tom Holland) and also historic fiction (by the likes of the brilliant Robert Harris). Did you know that Cicero invented short hand? (QV, Ibid, etc, NB, and the rest of it)? Or rather, it was invented for him, by his slave, literary and legal assistant, confidant and advisor, Tiro.

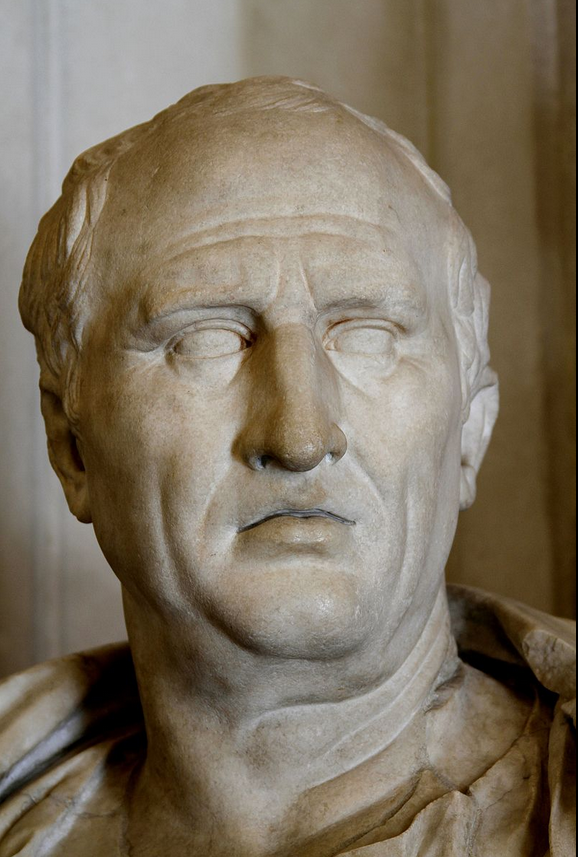

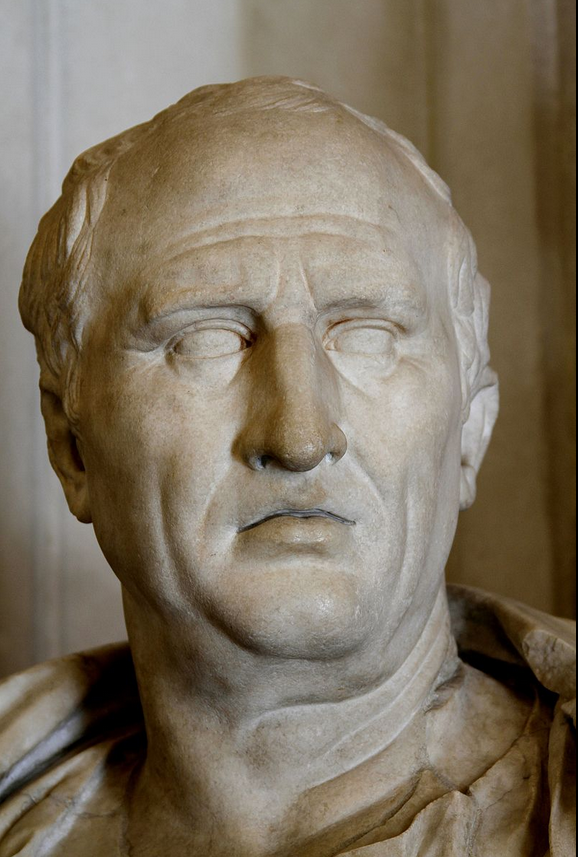

In any case, the bust by Scheemakers in the Long Room in Trinity College Dublin looks nothing like Cicero. We can say this with confidence because we have a pretty good idea of how Cicero looked, notably from this contemporary or near contemporary Roman bust below, from the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

Cicero : (Marcus Tullius Cicero) Bust from Capitoline museum, Rome, image Wikipedia Commons

Not the same chap as Scheemakers’ sculpture bust, one would have to say. So how did this happen? Should we blame the sculptor? Cicero was of course dead some 1,700 years before Scheemakers got to work. Even in terms of seeing the Roman bust above one appreciates it was not as easy in the 18th century to hop on a Ryanair flight to Fiumicino to go see such things. Nevertheless, Cicero is such a famous, such an iconic Roman, there would have been at least a reproduction, an engraving in all probability, of this above bust available to Scheemakers to see had he looked. One has to remember that 18th century scholars and gentlemen were obsessed with the figures of classical antiquity, they idolized them.

In fact, let me go further, I think Scheemakers did have a visual reference, or several, of Roman busts. But quite frankly, I think he got these images mixed up. Because Scheemakers’ bust of “Cicero” looks suspiciously like another, different, very famous Roman political figure from the late Republic. Specifically, it is very like Cato. I believe that Scheemakers went and got his figures and his reference drawings mixed up and this “Cicero” statue has been sitting for nearly 300 years in the Long Room with the wrong name and with everyone too polite to point it out. This figure in the Long Room gallery of sculpture busts (pictured again below) is really a mis-titled Cato, I’m sure of it.

above: Scheemakers’ “Cicero”

below: the actual Cicero

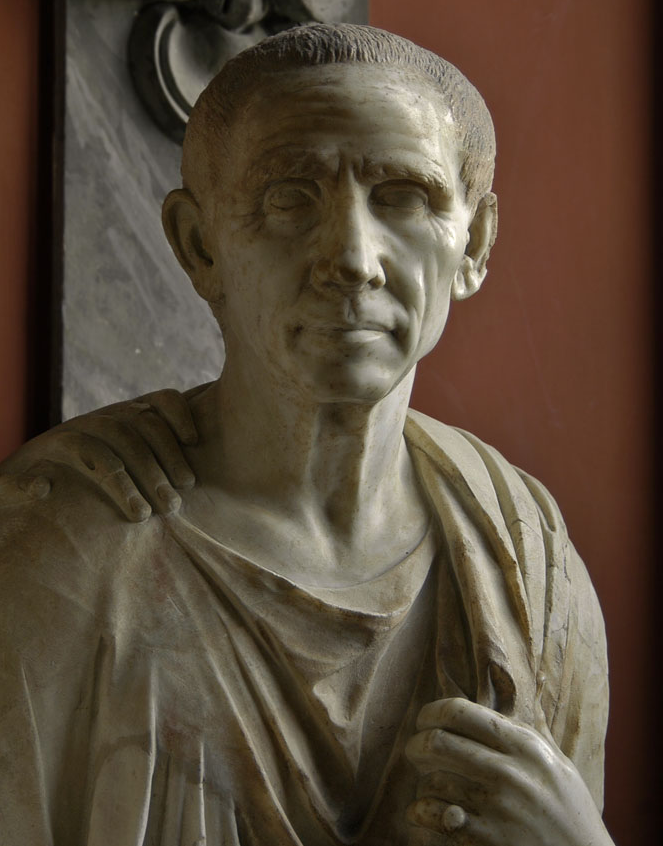

To help illustrate the point, below are two images commonly said to be of the actual Marcus Cato the Younger, the famous contemporary of Caesar and Cicero. Below image 1 is from a Roman stature commonly said to be of the actual Cato (Photo: Erich Lessing)

image 2 below is from a different Roman statue, also commonly said to be of the actual Cato. Photo S. Sosnovskiy.

above: a Roman era sculpture commonly said to be of the actual Cato, from the Vatican Museums, Pius-Clementine Museum, Gallery of the Busts. Photo S. Sosnovskiy.

It’s not credible that Scheemakers’ sculpture bears any resemblance to Marcus Tullius Cicero. Nor more to the point, that it even depicts Cicero. But it does seem likely it’s a likeness of Cato. A likeness that has somehow been mislabeled with the wrong inscription.

The real question then is whether the artist believed that he was creating a likeness of Cicero at the time of creation (because, for example, he may have had his visual reference material mixed up) or whether it is someone else’s fault. Is it possible, for example, that the well-known, busy artist provided only the sculpture busts without the identifying inscriptions? Is it possible that these carved inscriptions were later added by somebody at the University (possibly on the basis of a written list)? Is it possible that a clerical mix up of labels meant poor Cato ended up with the wrong inscription, and thus labeled as Cicero?

Cato, you can be certain, would have been disgusted. He may have walked around Rome in his simple black toga and bare feet to make a point about traditional Roman virtues. His great grandfather was the famous censor Cato the Elder, exemplar of just such values, But Cato was a Roman patrician and highly conscious of his dignity, fame, legacy and image. In other words he was very vain in his own odd manner. He would have hated to be bundled up or confused with the burly “new man” Cicero!

Perhaps more investigation and research will tell how the confusion came about. What is certain already is that this is not a statue of Cicero. It seems very likely that it is a statue of Cato the Young. These were two very important, but very different men, legendary in their own lifetime and revered for generations afterwards. They remain very famous people even to this very day. Perhaps, even now 250 years or so after these statues were ordered and installed, it’s still not too late to get their names right.

Background reading: factual

SPQR, Mary Beard

Caesar, Adrian Goldsworthy

Rubicon, Tom Holland

Historic fiction (highly researched and highly recommended)

Imperium; Lustrum; Dictator: the Cicero Trilogy, all by Robert Harris, superb, funny and fascinating, highly recommended.

I, Claudius; Claudius the God. Both by Robert Graves. Classic much loved historic fictional biography /autobiography.

Thanks for that nostalgia trip, Arran. It seems like nostalgia to me anyway, given how much the Romans are part of our common culture—thank you Will Shakespeare, Robert Graves…Ridley Scott.

LikeLike

Ciao Arran, posto molto interessante 🙂

buon inizio settimana

.marta

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gracia Transmedipensieri! Molto Gracia. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Source: solving an art historical mystery, in the old Library Trinity College Long Room. – Arran Q Henders… […]

LikeLike

Interesting article. I enjoyed the topic, even the tangent into Roman history. Needs a proof-read as there are several minor mistakes. It would be great to finally discover the truth behind the statue. One day. One day, maybe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks Garvan, delighted you enjoyed. We are moving home at the moment so afraid I wrote this in a but of a rush. (Mind you, I always make a few spelling errors, and many typos, rush or no rush) For the same reason, our house-move, only tonight did I finally get to sit down and do the much needed proof-read. Assisted by my better half! Anyway, thanks for reading and for your interest in the topic.

very best wishes -Arran.

LikeLike