These toy soldiers appear in the same exhibition as the First World War recruitment posters from recent post, although clearly the uniforms and equipment date from much earlier.

They come from France, currently on loan to Collins Barracks from the Musée l’armée, at the famous les Invalides of Paris. But as you see, these particular soldiers wear green. And that– as you may already have guessed- is because the soldiers depicted hail from the Irish brigade of the French army. These particular uniforms date from the very first years of the 19th century, from 1803 and Napoleon’s Irish Legion Légion irlandaise) – as the very good Wiki piece explains- a French light infantry battalion established in 1803 for an anticipated invasion of Ireland.

The colorfully dressed miniatures might look romantic, or even “cute” in miniature form. But that belies an extraordinary, long story of violence, exile, suffering and sacrifice.

On a point of dreary, historical fact soldiers of the French Irish Brigade never wore green; that was a contrivance of later romantic imagination. They generally wore red, (then black, in a later versions of uniform). But let’s not allow pedantic details get in the way of the main thrust here.

Who were these Irish Brigade of French troops? And, since Ireland was part of the United Kingdoms, frequently at war with France, what on earth were Irishmen doing in France anyway, fighting for “the enemy”?

The tradition of Irish troops fighting for France goes back a long way before Napoleon. If you look up the Irish Brigade on Wikipedia you’ll be told it began in 1690 during the Williamite war. In fact the first Irish regiments go back even further than that. They were sent to the French twenty years before that, (albeit secretly) by an English king, somewhat incredibly, by the Stuart king Charles II, in return for cash.

Following Charles II making the secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV in 1670, they were raised, predominantly of Catholics in Ireland then (covertly) sent direct to France. Most were in two regiments.

Louis XIV. king of ramce & most powerful monarch in 17th & early 18th century europe.

Almost certainly this is where Patrick Sarsfield, among others, first gained military experience- either Monmouth’s regiment of Foot or Hamilton’s Irish Regiment- (probably from around 1675 in Sarsfield’s case). Catholics were forbidden and excluded from holding officer commissions in the British army by dint of the hated Test Acts, so this was a very rare chance to follow the natural vocation of many young men of their class.

above: Patrick Sarsfield, 1st earl of Lucan, Jacobite brigadier of cavalry, later a marshall of France.

Later, Charles II’s brother and heir, James II did the same trick. Remarkably, both kings kept this “present” to the French secret from their own UK parliament, which was fearful of and hostile to France. Had the Stuarts asked for parliament’s permission, it certainly would have been refused. As you can imagine, if Catholics were forbidden even from commissions in the British army, as for them shipping to France…

James II, last Stuart king of England.

It was bad enough France was a large, rival power; it was militantly catholic as well. Under Louis XIV, it persecuted then, (in 1685) effectively kicked out its Huguenot minority of Protestants.

The gigantic, threatening figure of Louis XIV was unlikely to endear himself to a London government keen on civil liberties and royal prerogative checked by democratic controls. Louis le Gran was the archetype and ne plus ultra of absolutist monarch. Famously, being queried by some courtier anxious for the welfare of the realm, he reputedly quipped- l’Etat? c’est moi. : The State? that’s me” or (my preferred translation): “I am the bloody state”.

But, to the British the idea of Irish troops in France was even more menacing than all that. Through his long, successful reign Louis massively swelled French boarders through an aggressive expansionist policy of military force, happily carving off parts of Germany, Italy, Spain, Flanders and elsewhere.

Naturally this included threats to small, plucky protestant Holland, (led by William) who many English saw as their “natural ally”. By the second decade of his long reign, the whole of Europe lived in fear of France, Europe’s preeminent super power. England was no exception.

Except for its Stuart monarchs, that is. Charles II and his brother James II had grown up in France, sent there for safety as children during the English Civil War. There in exile they heard the news of their father’s execution, decapitated on the block at Whitehall. France was their childhood home, a refuge from the violence of England. So when later gained the English throne, they certainly didn’t share their subjects’ generic loathing of France.

Nor did they share their subject’s generic, often hysterical dread of Catholicism. Just the opposite in fact: Charles converted “to Rome”on his deathbed. His brother James did so much earlier in life. Thus after Charles’s death, James II came to the throne openly, avowedly Catholic, (the first such British monarch in over a hundred years), much to the horror and disquiet of most of his subjects. There was many dark muttering of a Papist succession.

The exception, naturally, was in Ireland, where hard-pressed people rejoiced, looking forward to restored civil and religious liberties, (soon underway in James’ reign) and to restoration of lands, confiscated at the time of Cromwell.

None of this explains fully why the Stuarts sent Irish troops to France. But then, the last two Stuart kings of England were slippery, duplicitous characters. Their exact motivations are often difficult to read, even through the clarifying, long lens of history.

As their father Charles I paid dearly for his icy disdain of Cromwell’s Parliament with his head on the block, you might think this grim fact would check his sons’ actions after the Restoration. Instead they chaffed at restraints imposed by parliament. They looked enviously across the channel to their cousin Louis, his magnificence and utter lavishing splendor, ruling supreme and unchecked, either from his rustic country retreat, Versailles, or his modest town-house, the Louvre.

So, I have one theory as to their motives. Unusually for British monarchs, who normally tend towards the pompous, the conventional, the dowdy and the dull, the Stuarts did at least have some taste. Charles I was a patron of Rubens and Van Dyck, effectively bringing Renaissance and Baroque art to dowdy, timber frame England.

His sons were the same, partially a product no doubt of their continental upbringing. Charles II in particular, had expensive but excellent discernment in music, architecture, painting and theatre. He proved a lavish and important patron of the arts and sciences, reviving the entire London theatre and dramatic arts scene, commissioning Christopher Wren’s Saint Paul’s cathedral and founding the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Truly, after the joyless puritanism of the Commonwealth, this was a restoration in more ways than one.

Saint Pauls cathedral, rebuilt, like most of central London after the Great Fire, by order of Charles II & the last word in the (belated) English baroque. Sir Christopher Wren. Built 1675-1708.

So it was a source of acute irritation to the Stuarts as Parliamentarians, whether Whig grandees, or (shudder) rump Puritan types, controlled the royal purse, cramped their style and patronage and always thwarted attempts to raise extra funds through various taxes and levies.

In other words, the Stuarts may not have really been conspiring at the destruction of protestant, democratic England as they sent clandestine Irish troops to Louis. They may simply have been sulking. They may simply have done it for the large bags heavy with French gold. In James’ case, he also had to protect himself against waves of treasonous conspiracy.

Over in France, the first Irish soldiers were not well treated by their new French employers. They tended to be used as shock troops, thrown early into the fray, and thus suffering disproportionate causalities. But they did gain respect. Those who survived (Sarsfield for example) eventually returned as experienced, battle-hardened, veterans, something with huge implications for the later, Williamite War in Ireland (April 1689- September 1691)

That war began soon after James was deposed by William and Mary. As the bloody contest raged in Ireland, between the Jacobites, that is the supporters of James II (and all, later Stuart causes) and the Williamites, even more Irish troops were sent to France, this time in exchange for French infantry sent the other direction back to Ireland. About 5000 Irish men went to France, originally in five regiments under five colonels, later merged into three (under colonels Lord Montcashel; O’Brien and Dillon) the French replacements took their part in the war, and were present in large numbers at the Battle of the Boyne amid James’ Irish army.

contemporary depiction, Battle of the Boyne, County Meath, Ireland, July 1690.

Some people think the war was mostly over after the James lost the Battle of the Boyne. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. The war raged on for well over a year, including various sieges, ambushes, skirmishes and major pitched battles as towns and cities were taken and recaptured, crossings held or lost. The Jacobites only lost the war a year later, after the Battle of Aughrim.

The Battle of Aughrim, at County Galway, the most ferocious, bloody and costly battle ever fought on Irish soul, victory finally swung the war for the Williamites. A vivid depiction of by Victorian Irish artist John Mulvany, 1881.

After defeat at Aughrim, the surviving Jacobites turned once again fro Limerick, whence began the second siege of Limerick. With the loss of thousands of casualties, dozens of their senior officers lost or killed, as well most of their weapons and nearly all their artillery, the Jacobites now had little chance of surviving another long siege, and no chance whatsoever of successfully breaking out in order to prosecute the war again. Nor was further help arriving from France.

In that context, their eventual negotiated surrender, under the terms of the new Treaty of Limerick, (negotiated chiefly by Patrick Sarsfield) was a diplomatic coup. But it led to the greatest exodus of Irish military personnel in history, as well as most of the remaining Catholic gentry and aristocracy.

In that tragic event, forever, wistfully remembered as the Flight of the Wild Geese, over 12,000 Irish infantry and the surviving squadrons of cavalry, marched out of the damp, crumbling walls of the city, in September with their arms and colours and shipped to France. The Anglo-Dutch Williamite army, under General Ginckel, was relieved to see them go.

There is a lot more to this story of course. How exactly the Jacobites lost the war in Ireland, and were thus forced into eternal, bitter exile, is one of the saddest but most gripping tales from this rain-soaked, storied little island of ours. We shall save it for a future post. What happened when the Wild Geese arrived from Limerick to France is what concerns us here.

The entire Irish army was at first kept intact, not at first as troops for Louis, but as Kings James personal army. Because plans were afoot for (wait for it…) a direct invasion of England itself. By May 1692, less than a year after Limerick, an the Irish army of 14,000, supplemented by thousands more French infantry and artillery, a combined army of over 20,000, stood ready for transport to the south coast of England by a fleet of 44 French ships of the line.

Unfortunately, due to gales off the Straits of Gibraltar, the ships of the French Mediterranean fleet were unable to join them, leaving them outnumbered by the enemy fleet. Under pressure to act, Admiral Tourville took the hasty and in retrospect disastrous decision to proceed and engage the enemy at sea, to clear the channel before coming back to collect the troops for the invasion. Instead, his ships were scattered, harried and torched by the Anglo-Dutch navy. Most Irishmen, waiting frustrated on the cliffs overlooking the engagement could only listen to the cannon and watch in agony. Most would never see home again. Nor would their descendants.

With their plans in ruins and with the prospects for a second Stuart restoration shelved for the time being, James’ Irish army-in-exile were now absorbed into the larger French one. They formed into an Irish brigade, further subdivided into five battalions or regiments. Each was named in turn after their regimental colonels, such as Dillon or Berwick, (James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick, the illegitimate but favored son of James II)

above: James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick, illegitimate but favored son of James II. A commander in the Williamite war and later a Marshal of France, who enjoyed a long, highly successful military career.

These Irish regiments and brigades kept their distinctive Irish culture, for generations, even the Irish language, as well as a deep grievance and keen hatred towards England.

They became an elite unit within the French army and fought in the Nine Years War; the War of the Spanish Succession and the War of the Austrian Succession. They scored several notable successes, for example in the Battle of Cremona in Northern Italy, (1702).

But the moment when they attained heroic, almost mythic status in France was 1745, following their crucial role at the Battle of Fontenoy, in May of that year.

The army of Louis XIV was pushing into the Low Countries. But troop numbers were greatly reduced when thousands of his troops were rushed off to face a threat elsewhere.

This reduction left them outnumbered by the combined Anglo-Dutch army sent to defeat them. Accordingly, on the day of the battle, the French army was having a bad time of it.

Then at a critical moment, the Irish brigade who, unusually, had been kept in reserve, was ordered into the fray. At this stage, many of the younger Irish officers and men were French-born, but they’d all maintained that keen sense of national cultural identity. You can be sure there was much talk of the broken promises of perfidious Albion in the ranks. “Remember Limerick” was the call. They charged the Anglo-Dutch flank and with all the tears of hurt and fury released, smashing into it.

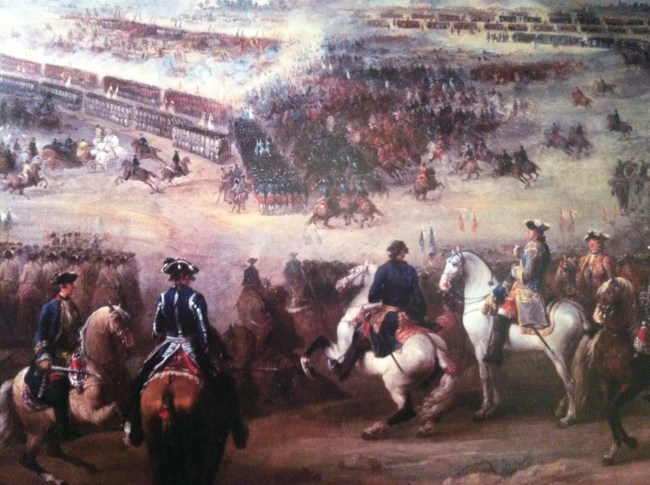

Contemporary depiction, Battle of Fontenoy, Flanders, May 1745.

They routed the English, capturing British colours (the flag standard) and ultimately forcing them from the field.

irish cavalry at Fontenoy in triumph, bearing captured British flag. The senior officer on right appears to be Berwick.

This confrontation turned the tide of war in the Low Countries. Irish troops carried the day at Fontenoy and wrote their names into military history. Overnight they were highly celebrated and became the toast of France.

Soon every self-respecting French schoolboy had a regiment of green- painted Irishmen, in his collection of toy soldiers. And here they are, in Collins Barracks today.

End.

Rave reviews and new testimonials, of both our walking tours and our famous How to Read a Painting workshop (twice a month at the National Gallery of Ireland) appear regularly on TripAdvisor. These reviews can be seen here.

Sources for my article above:

(recommended: ) Patrick Sarsfield and the Williamite War, Piers Wauchope, 1993, pub. Irish Academic Press Dublin and Portland, Oregon. (A really excellent book, admirably clear, balanced, fair, and yet with a thrilling sense of narrative. One of my favorite books on 17th century history in fact, a thrilling read)

Ireland: a History, by Thomas Bartlett, pub. Cambrridge University Press. 2010.

Modern Ireland, 1600-1972, author R.F. Foster. pub. Allen Lane, Penguin Press. 1988. and for quick fact/date spelling checking: Wikipedia, and other webpages, including Wild Geese Today, (US) etc.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed or found this article useful, please leave a comment, subscribe or share the link. If you quote text or use images from this article, (and no problem for any non-commercial use) but please acknowledge this source and provide a link back to it. Thank you. -Arran Henderson.

“If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten.”

– Rudyard Kipling, The Collected Works

I wish you’d been my history teacher back in school 🙂

LikeLike

well, better late than never, eh? I can do my best now. 🙂

LikeLike

Irish fighting with the French – guaranteed to get the English a little annoyed 🙂

Got sidetracked, I can see this is going to be slow deliberating process (can’t find a search bar ?)

David.

LikeLike

Ha, Hi david, yes, sorry about that. It’s silly but I have not or have not been able to install a search bar Widget yet. I’ll look into that again soon.

In the meanwhile, if you’re looking for that late 16t to 17th C material via a vis our chat earlier, you could start here, (on a Munster based planter called Richard Boyle) Then rather going back to the home-age/archive, (which i know takes an age) instead just scroll forward using the small forward & back “older post “newer/next post” button at the foot of the main text (above the comments etc)

Enjoy if you make it and find it ! 🙂

https://arranqhenderson.com/2012/11/27/saint-patricks-tour-3-a-shorter-post/

LikeLike

Nice article. However, these soldiers actually represent the Légion irlandaise (3e Regiment Etranger (Irlandais)) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Legion

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment and clarification. I didn’t mean that the toy soldiers (at the top) represented the earlier 17th century men, that period is represented here i the battle of Fontenoy painting. But I see what you mean, (about the tin soldiers) maybe it could be confused/ could easily be confusing and could be understood that way. I’ll amend the text to make it clearer as soon as i can. Thanks again for reading and commenting . -Arran.

LikeLike